Please Follow us on Gab, Minds, Telegram, Rumble, Gab TV, GETTR, Truth Social, Twitter

G. K. Chesterton, who wrote volumes of readable journalism, used to say, “Journalism largely consists in saying ‘Lord Jones is dead’ to people who never knew Lord Jones was alive.”

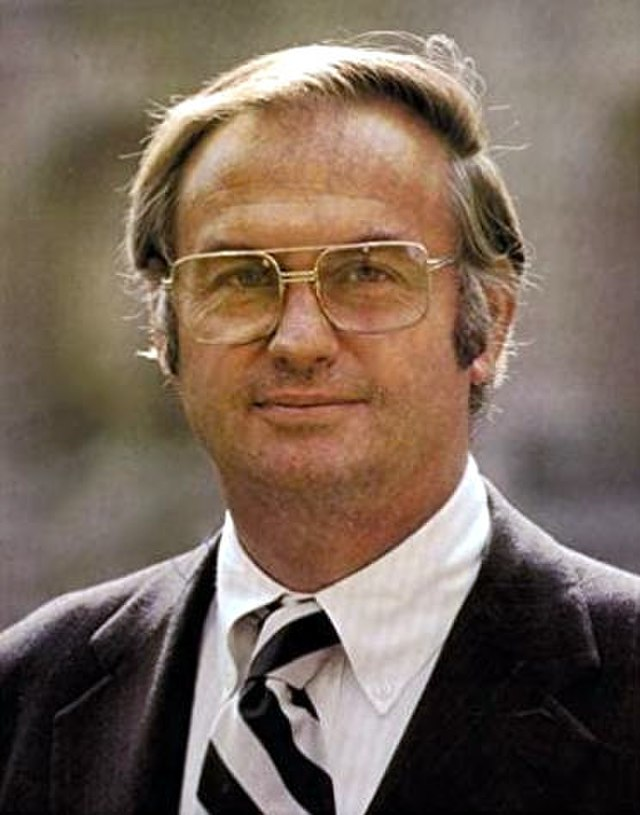

Former U.S. Senator and Governor of Connecticut Weicker never had that problem.

But memories are perishable. And politicians, many of whom like Weicker are rich, manage to live their lives in sequestered bubbles, none more comfortable than inflated media adulation. Wealth is, among other things, a protective cocoon, a safe place for the wealthy, so long as they are able to cling fiercely to their riches with sharp talons or, at the very least, with the help and advice of very expensive but always affordable accountants and lawyers.

Chesterton’s good friend, Hilaire Belloc, could say imperatively in a poem titled Advice to the Rich – “Get to know something about the internal combustion engine, and remember, soon you will die” – but politicians who live in the political moment have no need to worry themselves to a frazzle about impending death or final judgments. It is plain from the reportorial notes sounded in stories announcing his death that Weicker, a politician astute enough to know how to play both ends against the middle, did not worry overmuch about dying or a fabled “last judgment.”

The judgments that matter most to professional politicians such as Weicker -- in political office continuously for more than 30 years -- are those that may be found in the editorial sections of newspapers. On this score, Weicker has lived a blameless life. Editorials that shadowed Weicker’s long political journey were uniformly admiring and unquestioning.

Weicker was, as he mentioned in Maverick, an autobiography written by ghostwriter Barry Sussman, usually at odds with his own Republican Party – and not in a good way.

During his last year in the U.S. Senate, Weicker’s liberal ADA rating was 10 points higher than that of Chris Dodd. Weicker’s gradual move towards progressive Democrats was years in the making. The imposition on Connecticut of the Weicker income tax, a measure heartily resisted by moderate liberal Democrats such as former Governor Ella Grasso, is portrayed, in Weicker’s telling, as inevitable. To force the income tax down the gullets of Connecticut tax payers, Weicker had vetoed a number of balanced budgets passed by the General Assembly, many of whose members regarded an income tax as a license to spend. Time has proven them right. Connecticut’s present budget is more than three times larger than Governor William O’Neill’s last pre income tax budget.

Weicker had claimed in several interviews that his initial resistance to the prospect of an income tax – instituting an income tax in the midst of a recession, Weicker said during his gubernatorial campaign, would be like “pouring oil on a fire” -- was overcome by political reality. The state could not go forward, Weicker insisted once he was elected Governor, without an income tax.

What this really means is that the General Assembly, quickly moving leftward, always had been averse to permanent, long-term spending cuts – and that was why an income tax was in order. In Weicker’s estimation – though he was careful not to mention it -- increases in spending were irresistible; therefore, a new income tax was inevitable.

Nothing in politics is inevitable. The General Assembly has long lacked the courage to restrain its ungovernable appetite for spending. Weicker fueled the simmering fire. The new tax, the state’s present alarming state debt of $43 billion, and the general disposition of political forces in Connecticut are Weicker’s real and lasting legacy to his state.

At a press conference in 2020, the Yankee Institute reported, Governor Ned Lamont, Weicker’s political protégé, shouted from the rooftop the long suppressed truth concerning the state’s obscene pension debt, the largest per capita pension debt in the nation: “I got to tell you, debt and unfunded pension liabilities are a big deal. We probably have more debt and unfunded pension than any other state in the country.”

In 1991, the year Weicker’s pivotal income tax was passed, Connecticut was approaching an irreversible either/or moment. Either the state would control future budgets by painful permanent cuts in spending, or the state would increase revenue through the imposition of a new income tax. Weicker chose the road of tax increases often taken by timid legislators in Connecticut. A real maverick, alive to economic realities, would have cut spending, one of those awkward truths that almost certainly will not be mentioned in any of the maverick’s obsequies.