Please Follow us on Gab, Minds, Telegram, Rumble, Gettr, Truth Social, Twitter

The first rule in the political handbook is – never attempt to defend the indefensible. The attempt failed spectacularly during the Watergate imbroglio, the dreadful Dred Scott decision that found African American slaves were property rather than persons, and on many other occasions during America’s sometimes checkered history.

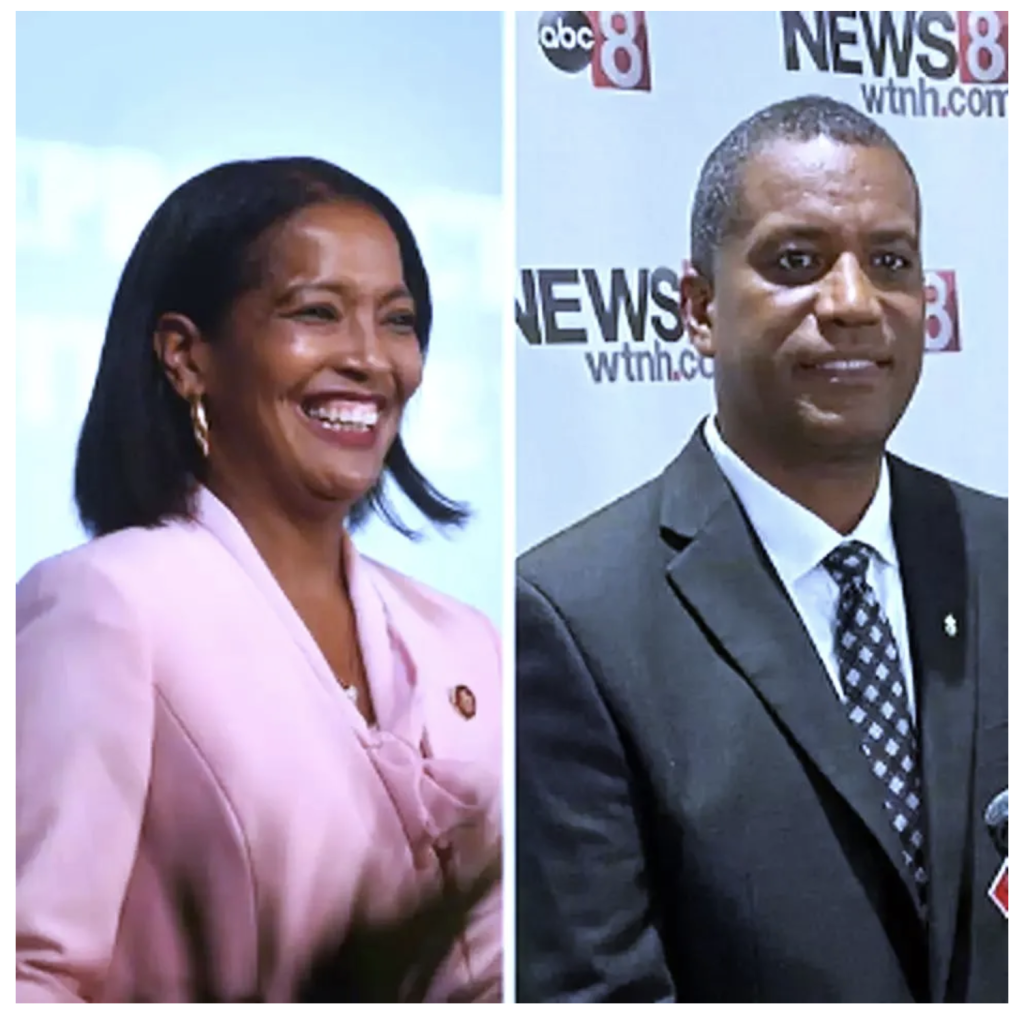

On October 2nd, the Hartford Courant carried on its front page an above the fold story – “GOP commercial blasts U.S. Rep. Jahana Hayes for her vote on fentanyl. Why she defends her stance” that should serve as a textbook example of the rule cited above.

The 30-second Republican commercial blasts Hayes as having voted against a bill in the U.S. House of Representatives, the “HALT Fentanyl Act”, a priority of the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration that, according to the Courant, “classified fentanyl in the most dangerous category of drugs… The measure called for classifying fentanyl as a Schedule 1 drug in the same category as heroin, LSD, peyote, and ecstasy, among others.”

“The commercial opens by showing a police raid as a narrator describes ‘an epidemic of fentanyl-related deaths’ in Connecticut.

“‘Yet,’ the commercial continues, ‘Jahana Hayes was the only member of Congress from Connecticut to oppose a bipartisan bill to permanently classify fentanyl in the most dangerous category of drugs,’ the announcer says. ‘The only one.’”

Elsewhere in the same story, state Republican chairman Ben Proto said of Hayes’ lengthy explanation, “If you’re explaining that much, you’re losing. … In the 5th district, where you have large cities like Waterbury, Torrington, New Britain, and Danbury, we’re seeing more and more drugs being purposely cut with fentanyl and young people who don’t know it’s cut with fentanyl, and it’s killing them … The very fact that you had Rosa DeLauro and John Larson — probably two of the more progressive members of that caucus — voting for [the bill] should tell you something. Her vote was bad. Her vote was wrong, and her vote is going to kill people in the 5th district.”

The very same October 2nd edition of the Courant carries another story – “CT man who sold fentanyl to woman who died of overdose pleads guilty to narcotics charge” – in which Meriden police “responded to a residence in the city on the report of a suspected overdose. Emergency crews found a 27-year-old woman unresponsive in a bedroom, federal officials said. She was taken to an area hospital where she was pronounced dead… Federal authorities said [the supplier who pleaded guilty] provided the woman with fentanyl she used hours before she died. She wrote in the text messages and in a journal entry that it was her first time trying fentanyl, officials said.”

A Connecticut Department of Public Health report disclosed in a 2023 data overview: “As of December, there were 1,331 overdose-related deaths in 2023, with 111 in January, 127 in February, 107 in March, 117 in April, 129 in May, 107 in June, 116 in July, 113 in August, 116 in September, 92 in October, 108 in November and 86 in December. Approximately 83.3% of these deaths involved fentanyl.”

These reliable figures demonstrate the lethality of fentanyl, certainly no secret to Connecticut politicians voting on issues related to the drug.

In the Courant story, Hayes disarmingly admits she had opened herself to political attack: “The NRCC [National Republican Campaign Committee] is correct. I was the only person in the Connecticut delegation who voted against it. At the time I took this vote, I knew it would be an attack ad. I was warned that it would be an attack ad, and I knew that it would be, so I’m not surprised.”

Then followed Hayes’ lengthy apologia: “My no vote was because this bill didn’t do anything to provide prevention, treatment, recovery, harm reduction, or money for law enforcement. Basically what it said was that anyone knowingly or unknowingly possessing fentanyl in any amount would have a mandatory minimum sentence with no discretion by a judge or anything. For me, I come to this work from a very different place than my colleagues. I saw what the 1994 crime bill did to decimate communities. I know that we cannot incarcerate our way out of a public health crisis.”

The notion that arrest, arraignment and, most importantly, conviction, sentencing and incarceration for crimes committed, lacks deterrent value flies in the face of centuries of jurisprudence, but it appears to have been warmly embraced by progressive Democrats such as Hayes who will not rest until every exception to a rule is fashioned into a rule. It has been generally accepted throughout history that exceptions prove the rule, and we do not want to throw out babies with the wash water. Conviction and internment work to prevent crimes.

The measure Hayes voted against would have brought fentanyl under the umbrella of a category of illegal substances that already requires mandatory minimum sentencing, including, according to the Courant “heroin, LSD, peyote, and ecstasy, among others.”

Hayes’ principle objection to the bill was, she said, that it provided “Only incarceration with mandatory minimum sentences with no discretion for the judge to even decide, based on the circumstances, if incarceration was warranted. … We tried this in the 1990s. It didn’t work.”

In the case of criminal prosecutions involving “heroin, LSD, peyote, and ecstasy, among others,” the American justice system allows judges wide discretion, and American law makes sharp distinctions between punishments assigned to users and sellers.

It is the business of a U.S. representative to write and approve laws. One cannot properly do that job if one makes no distinction between the baby and the wash water – between rules and exceptions. Would Hayes favor the automatic repeal of a law whenever the number of people convicted and incarcerated under the law reached a number unacceptable to Hayes?

We should not assume that every drug related crime is evidence of innocence because the criminal has ingested heroin, LSD, peyote, and ecstasy – or fentanyl, a deadly drug now folded into other drugs.

In fiscal year 2010, according to the U.S. Sentencing Commission, 15,274 criminal cases involved an offense carrying a mandatory minimum penalty. What would Hayes have us do with a robber who steals her pocketbook and then throws himself on the mercy of the court because he is a recreational heroine user?

Then too, there is a profound categorical difference, C.S. Lewis argues persuasively in “The Humanitarian Theory of Punishment,” between retributive justice, a product of the courts, and “merciful” or humanitarian forced therapy, a product of the psychiatrist’s couch.