Please Follow us on Gab, Minds, Telegram, Rumble, Gettr, Truth Social, Twitter

Exactly 210 years ago, John Quincy Adams gave his country something no other past, present or future president has ever given America as a Christmas gift—a peace treaty. On Christmas Eve, December 24, 1814, Adams literally gave the United States peace on earth.

The year 1814 was tumultuous. The USA was in the midst of its second war with England called the War of 1812. Although America and England had signed a peace treaty to end the American Revolution in 1783, the English government had continued to wage an economic war against the United States by failing to recognize the U.S. citizenship of American merchant sailors.

According to John Quincy’s estimates, British sea captains had kidnapped over 9,000 Americans since the 1790s and had forced many of them to serve the British. This practice, called impressment, was the moral outrage behind the War of 1812.

As 1814 neared completion, Americans were fired up over another outrage. On August 24, 1814, British soldiers had hurled flaming javelin rockets into the White House. The redcoats had burned the White House, the U.S. Capitol building, and almost all of Washington City’s government buildings. Led by British Admiral George Cockburn, the burning of Washington was the 9-11 of the War of 1812.

More than 40 days later in October 7, 1814, John Quincy Adams learned the agonizing news about the fires at his diplomatic post in Ghent, which is part of Belgium today. For months, he and a handful of American envoys had unsuccessfully negotiated with British diplomats. They’d failed to craft a peace treaty to end the war between America and England.

Their problems exploded when Adams’s brother-in-law, George Boyd, arrived at their hotel. Boyd had been sent on a ship to personally deliver the news of the burning of Washington City to John Quincy and the American commissioners. Boyd literally burst into his brother-in-law’s room to share the shocking news.

“The destruction of the capitol, the President’s House, the public offices, and many private houses is contrary to all the usages of civilized nations, and is without example even in the wars that have been waged during the French Revolution,” John Quincy fumed.

“The same British officers who boast in their dispatches of having blown up the legislative hall of Congress and the dwelling house of the president, would have been ashamed of the act instead of glorying in it, had it been done in any European city,” he declared.

John Quincy’s wife, Louisa, learned the news at the American embassy in St. Petersburg, Russia. In 1808, John Quincy had lost his seat in the U.S. Senate. That alone was enough to kill a political career of public service. Then his political enemies had sealed his electoral tombstone in 1809 by keeping him out of domestic politics altogether. They had sent him to St. Petersburg, Russia, as America’s first top diplomat to the czar.

A Congressman friend had called John Quincy’s Russian mission an “honorable exile.” Indeed it was. Adams and Louisa had lived in St. Petersburg for five years until April 1814, when he left Louisa in Russia to travel to Ghent to treat for peace with England.

“The news of the destruction of Washington makes much noise here [in St. Petersburg] and they seem to think . . . that all America is destroyed. Everybody looks at me with so much sorrow and compassion that I hate to stir out,” Louisa wrote John. “You would suppose that we had not a chance left of ever again becoming a nation.”

Lord Liverpool, the British prime minister, believed that the burning of Washington City was a game changer for the peace negotiations in Ghent. He calculated that the news would force Adams and the other U.S. peace commissioners to accept a new, lower boundary line to enlarge Canada’s land and diminish the United States. The prime minister concluded that the Americans in Ghent would not be “unreasonable” and would accept Britain’s 15-page settlement. The Brits’ plan would have turned Ohio, Michigan and neighboring land into Canadian provinces.

In addition to loathing this land-grab, Adams described the British peace diplomats as insufferable.

“It must indeed have been for some of my own sins or for those of my country, that I have been placed here to treat with the injustice and insolence of Britain,” he groaned.

Adams needed something to turn things around. Not only did he need a single phoenix, but he also needed a full fleet of phoenixes—something seismic—to save America and resurrect the peace talks in favor of the USA. Would Americans answer the call?

If John Quincy had plucked a dictionary from his book shelf, he would have discovered that phoenix was described as “resembling an eagle but with sumptuous red and gold plumage.”

Over the centuries, the phoenix myth was widely told. Poet John Dunne had used it in his 1633 poem, The Canonization:

“The phoenix riddle hath more wit. By us; we two being one, are it,” he wrote. By describing a phoenix as two being one, he touted the importance of working together in marriage to take on the world and overcome setbacks.

Going back much further to the first century in 96 A.D., Pope Clement I understood that the phoenix story was well known in his Roman culture and in the Middle East. He saw it as part of the natural world.

“Let us consider that wonderful sign [of the resurrection] which takes place in Eastern lands, that is, in Arabia and the countries round about. There is a certain bird which is called a phoenix,” Clement wrote in his letter to the Corinthians.

Clement used images from the Christmas nativity—the frankincense and myrrh given to baby Jesus by the wise men—to describe the spices on the phoenix’s funeral pyre.

“And when the time of its dissolution draws near that it must die, it builds itself a nest of frankincense, and myrrh, and other spices, into which, when the time is fulfilled, it enters and dies,” he continued.

The eagle-like phoenix then rises again, “in open day, flying in the sight of all men.”

Clement used this sign to help his fellow Romans two accept the resurrection of Christ. “Let us consider, beloved, how the Lord continually proves to us that there shall be a future resurrection, of which He has rendered the Lord Jesus Christ the first-fruits by raising Him from the dead.”

Thousands of years later, an English minister, John Flavel, used the images this way: “Faith is the phoenix grace, as Christ is the phoenix mercy.”

While not using the term phoenix, Old Testament prophet Isaiah tapped the image of an eagle to symbolize strength and rebirth: “They that wait upon the Lord shall renew their strength; they shall mount up with wings as eagles; they shall run, and not be weary; and they shall walk, and not faint.”

Fully aware of the eagle’s symbolism in the Bible and in culture, the Continental Congress adopted a free-flying eagle in 1782 to serve as a symbol of America on the Great Seal of the United States. Nothing held back the eagle. He was completely free.

In the fall of 1814, because the White House and Capitol were destroyed by fire, John Quincy knew that saving America now required a fleet of phoenixes to rise up and defeat Britain. That is exactly what happened.

Congressman Charles Ingersoll of Pennsylvania described the thousands of Americans who took action this way:

“The smoldering fires of the Capitol were spices of the phoenix bed, from which arose offspring more vigorous, beautiful and long lived.” Congressman Ingersoll

In the immediate aftermath of the burning of the nation’s capital city, Americans came together to defend their shores and save their country. A British army of ten thousand men left Canada to attack Plattsburgh, New York. They stopped at Lake Champlain to wait for their navy to arrive as backup. With only thirty-four hundred men, the Americans surprised their red-coated invaders by pushing back the royal fleet. As a result, America’s patriots secured a victory at Lake Champlain on September 11, 1814.

At the same time, Maryland ship owners sank twenty of their own ships across Baltimore’s channel, which made the water too shallow for Royal Navy warships to reach Fort McHenry. Fifteen thousand Americans, both militia and regular soldiers, stood ready on land to repel the British attack against Baltimore.

On September 13, 1814, the Royal Navy attacked Fort McHenry with bombs and rockets—the kind with a red glare—for about 24 hours. But because of the sunken merchant ships, the British Navy could not get close enough to destroy the fort. This, along with American sniper fire that killed the British commanding general, led the British Navy to give up. They fled the harbor and headed for New Orleans. The Battle of Fort McHenry inspired the lyrics of The Star-Spangled Banner, America’s national anthem.

When Louisa Adams learned about these glorious victories at her Russian post, she wrote: “Heaven has not deserted us, and if we do not desert ourselves we shall yet make our proud and insulting enemies feel that we are and must be a great nation.”

Her husband was determined to do just that, to treat for peace and save his great nation. After learning about American wins in Plattsburg and Baltimore in November 1814, Adams convinced his fellow U.S. peace envoys to take a proactive approach. They wrote a proposal of their own and gave it to their British counterparts.

Instead of lowering the boundary between Canada and America like the British wanted, Adams made a bold move, which potentially jeopardized his standing with his government, especially President Madison. John Quincy called for returning the Canadian-USA boundary line to where it had been before the war, known as antebellum.

This decision was tricky because President Madison had secretly instructed the U.S. peace commissioners to raise the boundary line into Canada to give America more land, not to lose land or return it to prewar boundaries. At first the other U.S. commissioners objected. But Adams used his lawyerly logic to convince them to propose returning the boundaries to their prewar status. Secretly defying President Madison’s original orders, they embraced a common sense course to peace.

By this time, November 1814, British officials realized that British Admiral George Cockburn’s decision to burn Washington City had backfired. European newspapers accused the British military of committing unpardonable atrocities by burning America’s government buildings, especially the books in the Library of Congress.

British leaders also realized that America had turned Russia into an ally, thanks to John Quincy’s recent diplomacy in St. Petersburg. The British prime minister bemoaned the American-Russian alliance by writing:

“I fear the emperor of Russia is half an American,” Lord Liverpool wrote.

Soon, a messenger carrying letters from the U.S. government arrived in Ghent in early December. Included was the most important piece of paper they could have possibly received in their hour of risk. President Madison had issued additional directions, proposing exactly what Adams had suggested for the boundary lines.

“In the instructions that we have now received, dated 19 October, we are expressly authorized to make the same identical [antebellum] offer. The heaviest responsibility therefore, that of having trespassed upon our instructions, is already removed,” John Quincy wrote Louisa with relief.

Over the days that followed, Adams had renewed optimism.

“For the first time I now entertain hope that the British government is inclined to conclude the peace,” he wrote to Louisa. “We are now in sight of port! Oh, that we may reach it in safety!”

They concluded the peace treaty just in time for Christmas.

On Christmas Eve, December 24, 1814, John Quincy Adams, the American commissioners and British commissioners signed the Treaty of Ghent, the peace treaty that ended the War of 1812 between America and England.

“I consider the day on which I signed it (the peace treaty) as the happiest of my life; because it was the day on which I had my share in restoring peace to the world,” John joyfully wrote to Louisa.

John Quincy gave his country what it most needed on December 24, 1814, literal peace on earth. This treaty secured a lasting peace between America and England. America and England have never been in an armed war against each other since then.

Because of the peace treaty, Adams emerged as a statesman. No longer a failed U.S. senator, he was now on track to become the U.S. ambassador to Britain, secretary of state, and then president of the United States. Like his countrymen and women who fought back against the British, the eagle-eyed Adams was also an American phoenix.

Many historians have called the War of 1812 the second war for American independence. Before the War of 1812, America had been a nation in name only after the American Revolution. Then after the 1814 Treaty of Ghent, Britain stopped the practice of impressment (kidnapping American sailors) and treated the United States as a separate, sovereign nation. America now took its place on the world stage, now widely accepted as an independent power.

Years later in 1818, Louisa compared the War of 1812 and the American Revolution in a letter to her father-in-law, former President John Adams. She concluded that the War of 1812 had solidified America’s position as an independent nation.

“I simply observed that the wars (the American Revolution and the War of 1812) had been so different in their natures that the officers in each had deserved the approbation of their country. And the effect produced throughout Europe by our late success and the change of sentiment, as it regarded the strength of our nation and the solidity of our government, might perhaps be as essentially beneficial as our struggle for independence.”

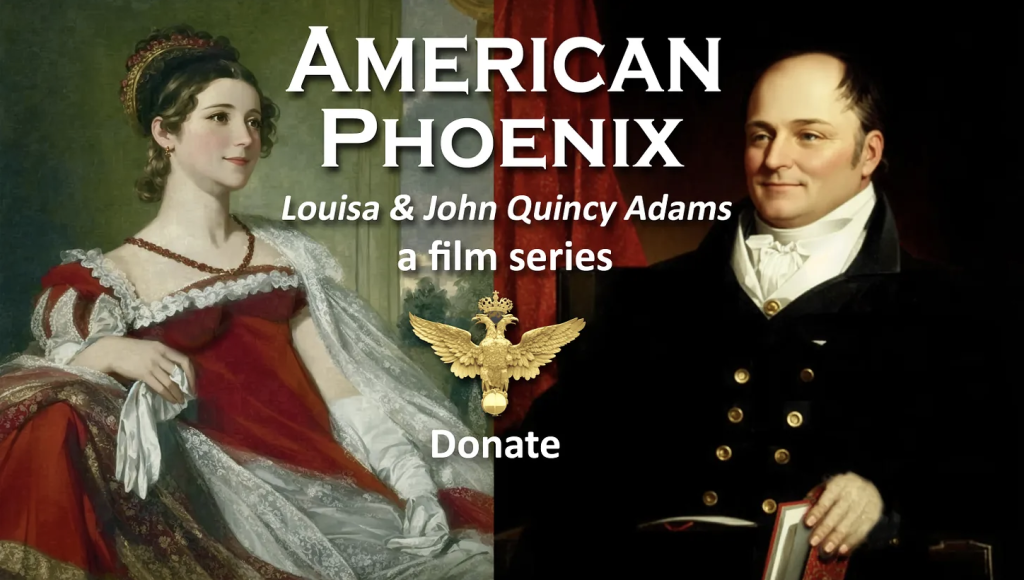

Proceeds from the 2025 American Phoenix calendar featuring Jane Hampton Cook’s favorite historical quotes go to the American Phoenix Film Fund to turn her book about John Quincy and Louisa Adams into a TV series.