Please Follow us on Gab, Minds, Telegram, Rumble, Gettr, Truth Social, Twitter

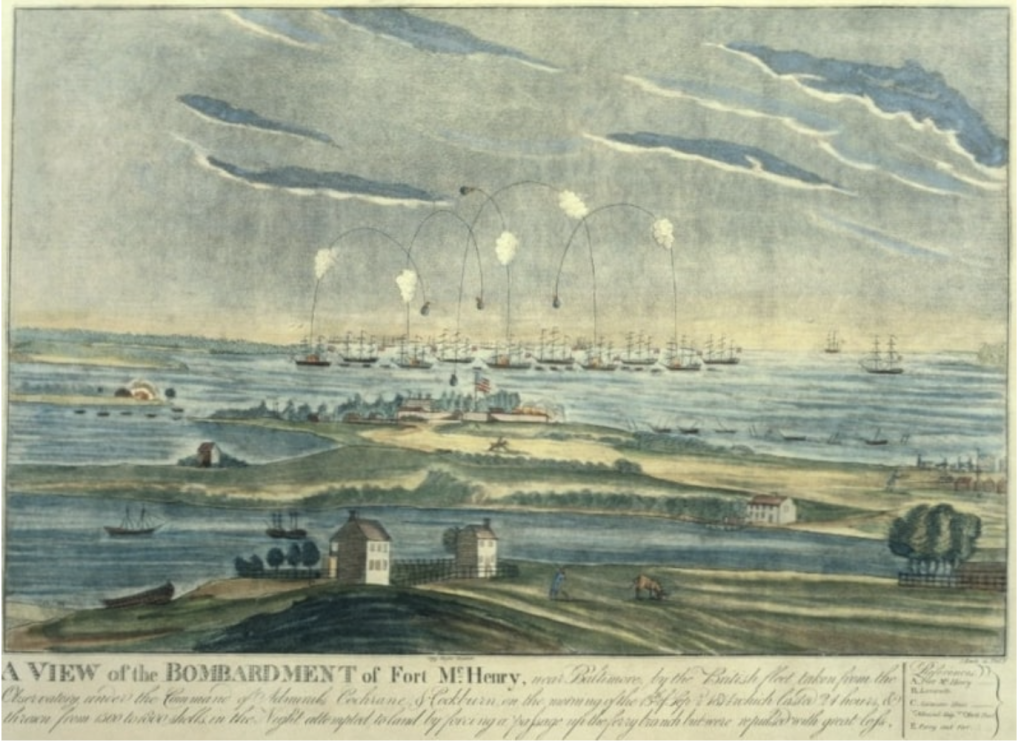

September marked the 210th anniversary of America’s national anthem, “The Star-Spangled Banner.” The public first read “The Star-Spangled Banner’s” lyrics in the aftermath of the Battle of Fort McHenry against the British in Baltimore, Maryland, on 13-14 September 1814.

Articles I found in GenealogyBank’s Historical Newspaper Archives show the birth of the lyrics in September 1814, and how the song became popular.

Many newspapers throughout the nation published an article called the “Defence of Fort McHenry.” The article’s author prophetically concluded that the song was so touching and universal that it would outlast the current moment.

This article reports:

The following beautiful and animating effusion, which is destined long to outlast the occasion, and outlive the impulse, which produced it, has already been extensively circulated. In our first renewal of publication, we rejoice in an opportunity to enliven the sketch of an exploit so illustrious, with strains, which so fitly celebrate it.

The annexed song was composed under the following circumstances – A gentleman [attorney Francis Scott Key] had left Baltimore in a flag of truce for the purpose of getting released from the British fleet a friend of his [physician William Beanes] who had been captured at Marlborough. He went as far as the mouth of the Patuxent [River], and was not permitted to return lest the intended attack on Baltimore should be disclosed.

What the article did not mention was that Francis Scott Key had opposed the War of 1812. He had not supported President James Madson or his war. Then after the British military burned the White House and U.S. Capitol on August 24, Key learned that his friend from Marlborough, Mr. Beanes, had been captured by the British military. Key put aside his political differences with Madison and asked for a meeting with him. President Madison gave Key permission to find the enemy and negotiate Beanes’s release.

When Key and Mr. Skinner, the U.S. Army’s prisoner of war negotiator, arrived at the British fleet, they met with British officers. Although the enemy agreed to release Beanes to Key and Skinner’s custody, the trio was not allowed to leave the British fleet until after the attack on Baltimore. The article continues:

He [Key] was therefore brought up the bay to the mouth of the Patuxent, where the flag vessel was kept under the guns of a frigate, and he was compelled to witness the bombardment of Fort McHenry, which the [British] admiral had boasted he would carry in a few hours, and that the city must fall. He watched the flag at the fort through the whole day with an anxiety that can be better felt than described, until the night prevented him from seeing it. In the night he watched the bombshells, and at early dawn his eye was again greeted by the proudly waving flag of his country.

Then the article features the lyrics, which were set to a popular tune called “Anacreon in Heaven.” The song and this article were published dozens of times in newspapers throughout the country over the next year, spreading the song’s popularity. Key’s poem has four verses, but only the first was used for the national anthem:

O say can you see, by the dawn’s early light,

What so proudly we hail’d at the twilight’s last gleaming?

Whose broad stripes and bright stars through the perilous fight

O’er the ramparts we watch’d were so gallantly streaming?

And the rockets’ red glare, the bombs bursting in air,

Gave proof through the night that our flag was still there.

O say does that star-spangled banner yet wave

O’er the land of the free and the home of the brave?

Soon Key’s new song caught on as a tribute to patriotism and was being called “The Star-Spangled Banner.” In October 1814 the Baltimore Patriot ran an advertisement for a historical play called Count Benyowsky. The evening would also feature a performance of Key’s new song.

This ad reads:

After the play, Mr. Hardings will sing a much-admired new song, written by a gentleman of Maryland, in commemoration of the gallant defence of Fort McHenry, called The Star-Spangled Banner.

The Treaty of Ghent, signed overseas in Ghent, United Netherlands, on 24 December 1814, ended the War of 1812 – although fighting continued until the U.S. Congress ratified the peace treaty on 17 February 1815. When news of the peace treaty spread, Americans celebrated. Back then, it was common to host dinners that toasted good news and heroes.

As the Western Citizen reported on 11 March 1815, “The Star-Spangled Banner” was one of a series of toasts given to celebrate the war’s end.

The toast:

“The star-spangled banner of Columbia – the proud guarantee of ‘free trade and sailors’ rights.’”

To top it off, Francis Scott Key’s new anthem for America was featured on the first Independence Day after the Battle of Fort McHenry. On 3 July 1815, the Daily National Intelligencer announced a theater’s plans for Independence Day, which included a performance of “The Star-Spangled Banner.”

This ad reads:

The celebrated song of the “Star Spangled Banner,” (written by F. S. Key, Esq., during the bombardment of Fort McHenry), by Mr. Steward.

In the decades that followed, “The Star-Spangled Banner” continued to be a popular patriotic song. Key knew that his song pleased Americans, but he never knew that it became the national anthem. On 3 March 1931, Congress passed a resolution naming “The Star-Spangled Banner” America’s official national anthem.

President Herbert Hoover signed the resolution into law and the rest, as they say, is history.