Please Follow us on Gab, Minds, Telegram, Rumble, Gettr, Truth Social, Twitter

We expect good journalism to be descriptive, and we expect such descriptions to accurately portray reality as it passes swiftly before us.

Here is New York Times commentator Ross Douthat describing potential Democrat President Kamala Harris’ “new way forward.”

Douthat knows that a “new way forward” must differ substantially from a preceding and discarded “old way.” Harris has been for nearly four years President Joe Biden’s Vice President. Therefore, a new way must differ in some important respects from Biden’s old way. Problem: American Vice Presidents in the past have tended to be shadows of the presidents under whom they serve, firmly attached to them as a tail is attached to a dog.

Douthat wrote in his column, “Sympathy for the undecided voter,” published in the Hartford Courant, that Harris has “offered herself [to the voting public] as the turn-the-page-candidate while sidestepping almost every question about what the supposed adults in the room have wrought across the last few years.”

These important questions, artfully evaded by Harris, touch upon “A historic surge in migration that happened without any kind of legislation or debate. An historic surge of inflation that was caused by the pandemic but almost certainly goosed by Biden administration deficits. A mismanaged withdrawal from Afghanistan. A stalemated proxy war in Eastern Europe with a looming threat of escalation. An elite lurch into woke radicalisms that had real world as well as ivory tower consequences, in the form of bad progressive policymaking on crime and drugs and schools.

“All of this and more the Harris campaign hopes that voters forgive or just forget while it claims the mantel of change and insists that ‘we’re not going back.’”

These few sentences by Douthat meet the test of good journalism cited above.

In passing, this writer may note that Douthat is not a semi-conscious Trump-thumper. Some of us wonder and worry whether Douthat may in the near future be defenestrated for ideological insubordination by the editor of the New York Times’ editorial page.

Harris, unvetted by both a primary campaign and an unusually tepid national media, remains a mystery a little more than six weeks before the general election. Her too friendly “interviews” are so far less useful as interrogatories than they are as fodder for campaign advertising clips.

Harris has straddled decisive issues on the economy, inflation and the imaginary U.S. southern border. Because her positions on important issues remain a mystery, she has no mandate to govern once she settles herself in the oval office. Former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton believes that mandates and proper vetting are unnecessary. Nancy Pelosi is famous for having said that the U.S. legislature must pass a budget so that we would know what’s in it. Similarly, the nation must elect Harris to the presidency before it knows what’s in her.

If Harris is successful in ridding the country of the “greatest threat to democracy since the Civil War” – only one of the silly charges leveled by the anti-Trump opposition – she will be the only president in U.S. history to enter the White House with an entirely free hand, unburdened by public party platforms, free of the usual political guardrails, and also unburdened by history. What can Harris’ pledge that the US should enter the future unburdened by the past mean other than, as Henry Ford once said, “History is bunk”?

Harris is not the only unexamined mystery awaiting resolution. Both political parties are shrinking in number, while the pool of unaffiliateds or independents is expanding.

But who are the independents? Are they expats from the nation’s two major parties or are they principled Thoreauians, parties of one, or Groucho Marxians who respectfully decline to join any party that would have them as members? The answer to such questions is important because we are told that most elections depend upon the independent vote.

If independents are expats from the two major parties, their votes may reflect their dissatisfaction with the party they have abandoned. It has been generally assumed that the independent vote is unpredictable. This may not be so. Parties in states that are predominantly Democrat – Connecticut is one – may want to tailor a party pitch to recover their lost sheep. Likewise Republicans in Connecticut may want to fashion a different political approach to those who have, for one reason or another, fled the majority Democrat party.

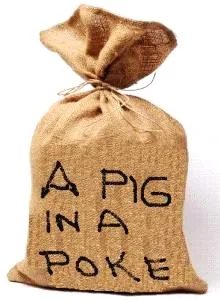

But in the absence of firm data – or at least a working profile of the independent voter – we are left with a mystery that any amateur Sherlock Holmes, armed with the right questions, might easily solve. Without a bit of hard delving, the path of independents and the path of future US foreign and domestic policies in a Harris administration are both pigs in pokes.