Please Follow us on Gab, Minds, Telegram, Rumble, Gettr, Truth Social, Twitter

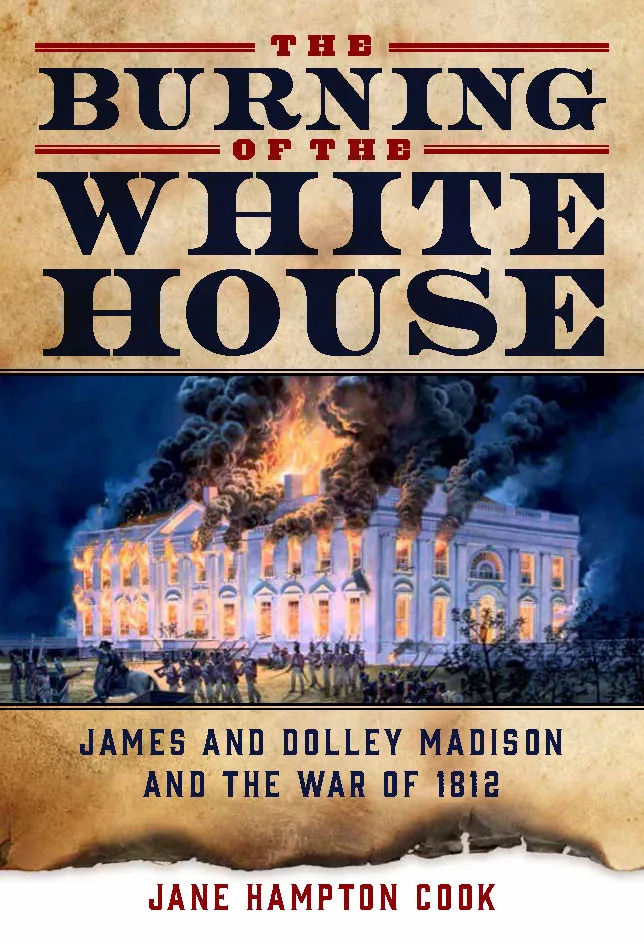

The collapse of Baltimore’s Francis Scott Key bridge has opened discussion about its namesake. Adapting original sources and letters, I wrote about Francis Scott Key and how he came to write “The Star-Spangled Banner” in my book, The Burning of the White House: James and Dolley Madison and the War of 1812. At the end of this article, I’ve included a notation to give you the historical context surrounding the controversy over two lines in the third verse.

Born in Frederick County, Maryland in 1779, Francis Scott Key attended preparatory school starting at age ten at St. John’s College in Annapolis, where his grandmother lived. He continued there through college and studied law after contemplating becoming a preacher. He found his calling in the law. Advocating for others proved as natural for him as breathing.

After graduation he became an attorney and set up shop in Georgetown, Maryland, just outside of Washington City. Francis Scott Key was also destined to be a family man. Marrying Mary Tayloe Lloyd, he became the father of eleven children.

Local residents in both Georgetown and Washington had read Key’s name in the newspaper many times, but not for heroics or politics. Instead, he took out classified advertisements such as this one in 1814: “A number of valuable squares, lots, and buildings in the City of Washington will be sold at public auction . . . at Mr. McEwen’s Hotel on the Pennsylvania Avenue.”

Key also had some business dealings with President and Mrs. Madison. In June 1810 he notified Mrs. Madison that their servant, Joe “has been anxious to purchase the freedom of his wife.” Millie, Joe’s wife, belonged to the Key family. Key had asked the Madisons to take in Joe’s his wife and child.

Appreciative of Millie’s excellent service, Key sought to give her freedom. “I have therefore at his request drawn up the enclosed deed of manumission.” Key would later become an advocate for creating a freemen’s colony in Africa.

Patriotic to the core, Key was also part of the Georgetown militia. On August 19, 1814, General Samuel Smith mustered the militia of Georgetown and Washington. At age thirty-five, Key was not the youngest but neither was he the oldest to answer the call of his country that day. The militia convened only to discover that they didn’t have enough weapons to do any good. They dismissed and rallied again the next day with a few more resources. Though still inadequately supplied, they marched nonetheless toward Benedict, Maryland. Combined with the Washington militia, their numbers totaled 1,800.

They were not alone when they arrived on August 22 at Battalion Old Fields, which was eight miles from Marlborough and eight miles from Washington. Joining them were Commodore Barney, his flotilla, marines, and regular soldiers from the 36th and 38th regiments, for a total of 2,700 men. Though far from the 10,000 that President Madison had hoped to convene, they were not a force of nothing. Under the circumstances, every hand that could help was welcome. At the same time, General Stanbury’s 1,400 men from Baltimore arrived in Bladensburg, Maryland.

On August 23, those camping at the old fields formed lines to show their readiness to march and fight. Hoping to motivate them, President Madison reviewed them.

General Smith knew that as an attorney Key was a natural advocate for others. In the crisis ahead, he would look to him for counsel and allow him to speak for him. Such as was the skill that Key brought with him wherever he went.

Francis Scott Key accompanied General Smith to Bladensburg. They were part of the advance group of militia, the rest of whom had gone back to Washington the night before and were now hurrying to the battlefield under the orders of General Winder.

Smith and Key discussed where to form the militia. Ever the advocate, Key offered to represent General Smith to the commanding general.

When General Winder arrived on the road near noon, Key approached him and offered Smith’s opinion that “several troops coming from the city could be most advantageously posted on the right and left of the road near that point.”

The problem was that Winder lacked a battle plan. Though he’d spent the past two months surveying the different locales within the 10th military district of Washington, he’d failed to war game or draft contingency plans. He didn’t have any pre-thought instructions of how to form battle lines if the British came to Bladensburg. Now all was haste with no time to waste.

Winder told Key that he’d defer to Smith’s judgment on where to locate the militia. What neither Winder, Smith, nor Key realized was this. The disorganization was so great and communication was in such disarray, that General Stansbury on the front line didn’t even know that Smith’s militia had formed lines behind him near the road to Washington.

Secretary of State Monroe also weighed in on the arrangements. He relocated Sterrett’s regiment, the Baltimore 5th, to an orchard, which was nearly a quarter of a mile from where the regiment originally formed. At the orchard they were too far away to cover the lines more exposed to the enemy. Colonel Beall’s 800 men from Annapolis also arrived so hastily that they were unable to identify a strategic position for aiding the main line.

Another phoenix to rise from the ashes of Washington lived in neighboring Georgetown. The news that Richard West brought Francis Scott Key, on September 1, 1814, was as distressing as it was unjust.

West lived in Upper Marlborough, where the British force had camped on their march to Bladensburg. His friend and neighbor, Dr. William Beanes, had allowed British General Ross and British Admiral Cockburn to use his house as their headquarters. In exchange for preserving his home, Beanes, a noncombatant, pledged to be peaceful.

When the British army trounced back to Marlborough in route to their ships after destroying Washington, several of them became disorderly. Fearing theft and arson, Beanes arrested a straggler. Furious that Beanes had broken their agreement, Ross ordered him arrested. Under the cover of night and without allowing him to change from his bed clothes into proper attire, British soldiers seized him from his home.

West had recently taken a letter from Maryland’s governor on Beanes’ behalf to British headquarters. Ross was unbending. Realizing that he needed an attorney’s penchant for advocacy, West then rushed to Georgetown to see Key, his brother-in-law.

What should they do? General Mason, who was responsible for prisoner of war exchanges, was aware of Beanes’ plight, as was Secretary Monroe. Beanes needed an advocate, one skilled in fighting for others using the weapons of logic, persuasion, and diplomacy.

Perhaps Georgetown’s Federal Republican newspaper rested on a table that day as West and Key talked in Key’s Federal-style multi-story house. That morning editors for the Federal Republican gave their readers a surprise. Instead of bashing the President. Madison’s war as they’d done numerous times—so much so that this same newspaper in Baltimore had played a role in the Baltimore riots that broke out after the war started in 1812—the editors printed an editorial called Peace.

Though still desiring a quick end to the war, they acknowledged that Americans now faced a new plight. Previous objections to the war and party preferences now needed to be set aside.

“The country must be defended, the invaders must be repelled. Infinite distress and misery, still deeper disgrace, will befall us, if the force sent to our shores, is not overpowered.”

Like the Federal Republican, Key wasn’t pro-war. He’d recently written his mother and bemoaned the fact that the war wasn’t going well. Not only was it not going well publicly, but it was also hitting him personally in the pocketbook. “The expenses of living here are enormous and the practice much lessened,” he explained to his mother.

He’d been thinking of joining his parents, who farmed and sold wool, in rural Maryland. “I really think I shall try to purchase a small flock of sheep in the spring, and if the war last on, I shall be obliged to leave this. I can come up to Pipe Creek and turn shepherd,” he’d suggested.

Yet, in his heart, he was a lawyer, not a herder.

“I have not determined upon anything but to stay here and mind my business as long as I can.”

With this mindset, he had stayed in Georgetown throughout 1814. Now, after the fall of Washington, what good was his law practice or farming if the British continued to burn and pillage American cities? Maybe he could do something by finding a way to help Dr. Beanes.

As the Federal Republican newspaper printed that day, the time had come to take up the mantel of the American Revolution. “It is absolutely necessary, unless the country is to be abandoned by the people. . . that every man should awake, arouse, and prepare for action,” the editors wrote.

Sorting out what led to the burning of Washington could come later. Now was the time for action.

In case any of their readers were shocked at their sudden change, the Federal Republican editors reassured them of their principles. Political discussion and a free exchange of ideas and opinions were essential rights. Those were now at stake as long as the British occupied the East Coast in any form. They’d received, from a reliable source, news that Admiral Cockburn and other officers were planning to attack again.

“The admiral has said distinctly ‘we must prepare for another severe struggle’ not meaning a single battle, but a series of hard contested fights. He says, that every assailable point on our sea coast will share the fate of Washington, and that there is no other place which will experience the same moderation and clemency.”

Instead of capitulating like Alexandria, each sea coast city must prepare to defend its citizens. It was time to “omit no sacrifice, spare no expense, to save the country. It is seriously threatened, and can only be saved by extraordinary exertions, such as our fathers made before us.”

The editors’ words reflected West and Key’s attitudes and concerns.

“No man who is mindful of what he owes his country and his own character, can advocate submission on, where resistance is practicable. The fight will now be for our country, not for a party.”

Key and West came up with a plan. Key would answer the call of his country. He wouldn’t directly take up arms, but would hold a flag of truce to advocate for Dr. Beanes. He knew where to start. Fortunately the man he most needed to talk to was now living with one of Key’s friends, former Congressman Cutts.

That same day, September 1, 1814, Madison’s pen continued to flow with vigor. He issued a proclamation to the American people.

“Whereas the enemy by a sudden incursion have succeeded in invading the capital of the nation,” he began, noting the lack of militia to defend it, “. . . they wantonly destroyed the public edifices. . . some of these edifices being also costly monuments of taste and of the arts, and others depositories of the public archives.”

He observed that all nations create memorials and monuments of historic value that should be respected. Madison let the American people know that Fort Washington, which guarded Alexandria, had been destroyed. They’d also received a letter from British Admiral Cochrane, which he’d written before the burning but Monroe didn’t receive it until afterwards.

“Whereas it now appears by a direct communication from the British commander . . . to be his avowed purpose to employ the force . . . ‘in destroying and laying waste such towns and districts upon the coast as may be found assailable,’” he continued.

He observed that the British claimed they burned Washington in retaliation for alleged destruction in Upper Canada by the U.S. Army. To Madison, this was merely a pretense, an excuse.

Perhaps more than anything, Madison was angry that the British had violated “principles of humanity and the rules of civilized warfare” during a crucial time, “at the very moment of negotiations for peace, invited by the enemy himself.” The president was determined more than ever “to chastise and expel the invader.”

Showing leadership, he continued by “exhorting all the good people thereof to unite their hearts and hands in giving effect to the ample means possessed for that purpose.” He asked all civil and military members to execute their duties and “be vigilant and alert in providing for the defense.”

He appealed to American’s patriotic devotion, so that “none will forget what they owe to themselves, what they owe to their country and the high destinies which await it.”

He also reminded them of “the glory acquired by their fathers in establishing the independence which is now to be maintained by their sons with the augmented strength and resources with which time and Heaven had blessed them.”

Sometime during the day, either before, after, or during the writing of this proclamation, the knock at the door came. Madison welcomed Mr. Key. He was well acquainted with him. Seven years earlier, he’d received a letter from Key and another attorney requesting his help. They’d been defense attorneys for a prisoner held in Washington’s marine barracks. The marine commandant and the navy secretary had prohibited them from meeting with their client. They needed Madison, who was then secretary of state, to intervene.

“We are constrained to trouble you on a subject which we have in vain endeavored to effect without your intervention,” Key had written back then in a letter to Madison. He could have used the same words to describe Beanes’ plight.

Key tapped Madison’s sense of justice. Both shared a passion for advocacy and the rule of law. Presenting a plan, Key proposed that he visit the British fleet under a flag of truce. Then he would try to secure Beanes’ release. The case was tricky to be sure, but it was something he had to do.

Swift and sure was Madison’s response. He agreed with Key and asked General Mason to intervene. Mason immediately wrote a letter on behalf of Beanes. He also gathered letters from wounded British soldiers, including a key officer, who were still recovering in Washington. These men wrote letters to General Ross proclaiming the good treatment that the Americans had given them. Mason then authorized Key to travel to Baltimore to join John Skinner, who was the U.S. prisoner of war exchange agent. Procuring a ship, together they would find the British fleet and do their best to secure Beanes’ release.

Hence, Madison played a quiet, behind-the-scenes role in the circumstances led to crafting the national anthem.

The dinner aboard the admiral’s ship on the afternoon of September 7, 1814, was the most surreal that Francis Key had ever experienced. He’d expected to meet with an officer or two, perhaps the captain of the ship, but not with the supreme commander. Now he was here with his American counterpart, Mr. Skinner. Together they dined with Admiral Cochrane and General Ross aboard the admiral’s flagship the Tonnant.

The day before in a small boat carrying a flag of truce, Key and Skinner had swept alongside a smaller British vessel, the Royal Oak. From there they’d followed the Royal Oak to find the admiral’s flagship further South in the Chesapeake Bay. Cochrane discovered their intentions right before his dinner on September 7. Not wanting to delay and in a hospitable mood, Cochrane invited them to join him and General Ross.

At first all was pleasantries. They engaged in small talk while they ate. And given the circumstances, what else could they discuss? Finally, the captain of the fleet hurled an insult at America. Skinner fired back.

Key was unimpressed, as he later wrote: “Never was a man more disappointed in his expectations than I have been as to the character of British officers. With some exceptions they appeared to be illiberal, ignorant, and vulgar, and seem filled with a spirit of malignity against everything American. Perhaps, however, I saw them in unfavorable circumstances.” Indeed he did.

With insults flowing faster than the wine at that dinner, General Ross intervened and offered to speak privately with Mr. Skinner about Mr. Beanes. This disappointment left Key out of a key conversation. All he could do was wait and hope that Skinner could prevail upon Ross to release Beanes.

He knew, however, that Mason had given them a good strategy. If Ross argued that Beanes had violated his pledge to refrain from hostile acts, then Skinner would respond that Ross’s first withdrawal from Marlborough had relieved him of that pledge. The next strategy was to present letters from wounded British officers and soldiers testifying to the humane treatment they were receiving from the Americans. In this way, Ross could release Beanes in the name of good will.

If those strategies failed, then Skinner and Key were authorized to give Ross a receipt for Beanes as if he were a prisoner of war and release a British war prisoner in return. This approach, however, could open a Pandora’s box by giving the British permission or justification to start hauling off other unarmed citizens for the sole purpose of releasing of genuine British prisoners.

Key later learned what happened as Skinner and Ross met. Skinner presented the case for releasing Dr. Beanes. Ross silently read the letters from General Mason and the British wounded.

“Dr. Beanes. . . shall be released to return with you,” Ross replied, pleased with the treatment the British wounded were receiving from the Americans.

Ross wrote a letter to Mason.

“Dr. Beanes having acted hostilely towards certain soldiers under my command, by making them prisoners when proceeding to join the army, and having attempted to justify his conduct when I spoke to him on the subject, I conceived myself authorized and called upon to cause his being detained as a prisoner,” he explained, not backing down from his original claims.

Then he acknowledged civility.

“The friendly treatment, however, experienced by the wounded officers and men of the British army left at Bladensburg enables me to meet your wishes regarding that gentleman.”

Ross promised to release him, though he believed he was justified in retaining him.

“I shall accordingly give directions for his being released. . . but purely in proof of the obligation which I feel for the attention with which the wounded have been treated.”

Skinner and Key’s joy at securing the release of Dr. Beanes lasted only a second or two. Earlier that morning, Cochrane had made a decision. He was going to attack Baltimore. Why the change? The promise of plunder and intelligence made the difference. After the attack on Washington, he’d sent out another British raiding party to rural Maryland. Though the commander, Sir Peter Parker, had been killed, his men brought back valuable plunder and supplies. They also brought intelligence that attacking Baltimore would be easy. The American will to fight was weak.

Hence, while Mr. Beanes would be released to them, Key and Skinner couldn’t leave until after the attack on Baltimore.

Cochrane said to them “Ah, Mr. Skinner, after discussing so freely our preparation and plans, you could hardly expect us to let you go on shore in advance of us.”

With no room left on the crowded Tonnant, Cochrane put Key and Skinner aboard the boat Surprise, which tugged their truce boat. For now they were stuck, held hostage in a British convoy and witnesses to the next attack.

As one who didn’t support the war, Key felt conflicted. Baltimore was not his favorite place. He despised the pro-war riot that took place there at the start of the war and led to the deaths of Revolutionary War veterans who opposed the war.

“Sometimes when I remembered it was there the declaration of this abominable war was received with public rejoicings, I could not feel a hope that they would escape,” Key later recalled.

But Baltimore was a family place, too. He knew it was filled with innocent women and children and Americans seeking to live a quiet life.

What worried him was Cochrane’s pledge to give Baltimore the Havre de Grace and Washington treatment.

“To make my feelings still more acute, the admiral had intimated his fears that the town [Baltimore] must be burned, and I was sure that if taken it would have been given up to plunder. I have reason to believe that such a promise was given to their soldiers. It was filled with women and children.”

All he could do was wait, watch, and pray.

Twelve days had passed since he’d first approached President Madison about rescuing Beanes. By the morning of September 13, Key knew something was imminent. Cochrane had ordered him and Skinner off the Surprise and onto the truce boat they’d taken to find the fleet. Then the admiral left the larger Tonnant and made the small Surprise his flagship.

Another sign that things were changing was Dr. Beanes, who’d now joined them aboard the truce boat. A nearby armed ship kept them under surveillance, ready to fire if the truce boat tried to slip away. This, too, was another indication that the British were reading for an imminent attack.

At 6 AM Cochrane ordered five bomb ships—the Aetna, Devastation, Meteor, Terror, and Volcano and other war vessels to move into a line 2.75 miles away but facing Fort McHenry.

Fire! The order came. The shots dispersed but they were too far away to hit the fort. Move closer! The ships moved closer; two miles away. This distance would have to do. The fort’s long guns prevented the British rockets from getting any closer without risk of cannonballs crushing their planks.

From his position eight miles away, Key could hear the shots. With a spyglass he could also see them. The blasts continued with a near rhythmic consistent pace. Each bomb ship hurled five bombs an hour. These bombs were spherical 10- and 13-inch shells that showered shrapnel upon exploding. Some fell short; some long. Others burst directly over the fort.

Key could see additional weapons besides the bombs. The British schooner Cockchafer and the rocket ship Erebus also fired rockets. At 8:40 AM U.S. artillery hurled cannonballs into the Cockchafer’s main sail and ripped it to pieces. What did Cochrane do? He wisely withdrew the Cockchafer.

What Key couldn’t ascertain was how many men Major Armistead, Fort McHenry’s commander, oversaw. Though the Americans clearly returned fire, their guns couldn’t reach the ships. While he couldn’t know what was going on in the fort or how many bombs were reaching the fort, he could discern that a white flag of surrender hadn’t appeared the fort. All he could see was a small U.S. flag, a speck in the distance.

After twenty-five hours of ear-piercing terror from bombs, the silence that followed after 7 AM on September 14 was welcoming but hardly golden to Francis Scott Key’s ears. What colors would he see as he placed his eye behind the spyglass and pointed it toward the fort? He didn’t know which was worse, beholding the British Union Jack flag above Fort McHenry or the white flag of surrender. Both would mean victory for the British and capitulation once again from his countrymen.

Suddenly he noticed it. Gone was the American battle flag measuring 17 by 24 feet that had flown over the fort. Instead, he saw the most beautiful colors cast against a canvas of a multi-hue sunrise. The stars and stripes, fifteen of them to represent that nation’s fifteen states that had grown to eighteen by this time, flapped briskly from the fort that morning. The sight could only mean one thing. The Americans still held Fort McHenry.

The flag that Key saw that morning measured 42 feet by 30 feet. It was the largest flag ever flown at a U.S. fort.

Months earlier General Armistead had requested that Fort McHenry “have a flag so large that the British will have no difficulty in seeing it from a distance.”

Commodore Barney and another officer had enlisted the talents of flag maker Mary Pickersgill. She made two flags, the smaller storm flag and the giant ceremonial flag. On that morning Key saw the larger flag, whose bright stars measured 24 inches from point to point. What he couldn’t have heard that morning was the music at the fort. Because America lacked an official national anthem, the band played the popular Yankee Doodle.

What came next, Key didn’t know. He was still hostage to the British fleet. Soon the word would come. Anchors away. Finally, they were free. And as he sailed, his emotion gave way to words, poetic words that fit a familiar pattern. Sometimes words born from deep emotion come like a flood, pouring so fast it’s hard for the writer to catch them all. Sometimes the words come like pieces of a puzzle, in bits and phrases that need to be put in a special order to fit the cadence of the tune in the writer’s head.

But the words came. “O say, can you see, by the dawn’s early light, what so proudly we hailed at the twilight’s last gleaming?”

The flag took center stage.

“Whose broad stripes and bright stars, through the perilous fight” as did the sight of the bombs and rockets. “O’er the ramparts we watched, were so gallantly streaming! And the rockets’ red glare, the bombs bursting in air.”

The endurance of 25 hours “gave proof through the night that our flag was still there.”

Suddenly Fort McHenry didn’t just represent Baltimore. It symbolized America, as did the 1,000 men who defended it. Suddenly the flag didn’t just soar over Baltimore, it unfurled over the entire United States.

“O say, does that star-spangled banner yet wave, O’er the land of the free and the home of the brave?”

The verses poured from Key’s pen, including lesser-known flourishes that reflected faith:

“O thus be it ever, when freemen shall stand, between their loved homes and the war’s desolation! Blest with victory and peace, may the heaven-rescued land. Praise the Power that hath made and preserved us a nation.” Some were surprising for a man who seemed to oppose the war: “Then conquer we must when our cause it is just, and this be our motto: ‘In God is our trust.’” Each verse ended with the refrain “and the star-spangled banner in triumph shall wave o’er the land of the free and the home of the brave!”

Key enlisted the tune “To Anacreon in Heaven.” The melody was familiar to him. After all, he’d written lyrics for it seven years earlier in 1806 in another song called “When the Warrior Returns.” It was the tune for the well-known “Boston Patriotic Song,” which was also called the “Adams and Liberty Song.” Years earlier when John Adams became president, his friend Robert Treat Paine, had written lyrics celebrating America and his presidency. Paine chose “To Anacreon in Heaven” as the tune. The song was the theme for a gentlemen’s club in London, the Anacreontic Society, named after Anacreon, a lyric poet from Greece.

Whether the words flowed easily for Key that day or came to him in bits and pieces to organize into a poetic pattern, one thing is for sure. The result spoke of the emotion that he and so many other Americans felt to learn that they had indeed once again defeated the British.

After the darkness of the burning of the U.S. Capitol and the White House came the dawn brought by the soaring multitude of phoenixes that awakened and defended Baltimore. Hope was brighter than ever. Maybe, just maybe, the Royal Navy would soon abandon America’s shores.

After arriving in Baltimore and spending the night at the Indian Queen Hotel on September 16, Francis Scott Key shared his lyrics with one of his brother-in-laws, Judge Joseph Nicholson, who’d led men under orders from General Smith. Nicholson arranged for anonymous publication of Key’s poem. They used the title “Defense of Fort McHenry.”

The poem was electric, popping up in newspapers across the nation. Washington Irving, who served as editor of a magazine, printed it as well. When Key returned to Georgetown, he had the pleasure of reading his poem in his hometown newspaper. Once again, Georgetown’s Federal Republican continued their renewed patriotism. Not only did they publish all of the verses, but they also published Key’s story, though without naming him.

“A gentleman had left Baltimore in a flag of truce for the purpose of getting released from the British fleet, a friend of his who had been captured at Marlborough . . . . and he was compelled to witness the bombardment of Fort McHenry, which the admiral had boasted that he would carry in a few hours, and that the city must fall.”

Key never personally experienced the notoriety that would later come to him, though his Georgetown paper accurately relayed his emotions. “He watched the flag at the fort through the whole day with anxiety that can be better felt than described, until the night prevented him from seeing it. In the night he watched the bomb shells and at early dawn his eye was again greeted by the proudly waving flag of his country.”

His poem would soon become known as the Star-Spangled Banner. Over time the song became especially popular with the military. By 1917 the U.S. Army and U.S. Navy had declared it as the national anthem for ceremonial occasions. After a series of campaigns from patriotic groups, Congress designated “The Star-Spangled Banner” as the nation’s official anthem and President Herbert Hoover signed it into law on March 3, 1931.

Historical context behind the third verse: In recent years, Americans have questioned the meaning of Key’s reference to slavery in the third verse: “No refuge could save the hireling and slave, From the terror of flight, or the gloom of the grave.”

Most of Key’s lyrics are universal, especially in the first verse. The relief of an American victory can apply to Fort McHenry in 1814 and many subsequent victories in American history. The third verse, however, requires historical context to understand what Key meant.

Just a few months before Key wrote these lyrics, the British military had issued a proclamation promising freedom to slaves who would run away. There was a catch, however. The male slaves had to first fight as soldiers in the British army before they could receive their freedom in Canada or the Caribbean.

Key did not think the British army was a suitable place of refuge for slaves or hired mercenaries. By fighting in the British army, they risked both the “terror of flight” and the “gloom of the grave.” Hence, these lyrics are not Key’s opinion justifying slavery but a reflection of the stakes of being forced to fight in the British army.

It also helps, too, to understand why America and Britain were at war in the first place. The primary moral issue behind the War of 1812 was impressment. British sea captains were kidnapping American sailors and “impressing” or forcing them to serve in the British Navy against their will.