Please Follow us on Gab, Minds, Telegram, Rumble, Gettr, Truth Social, Twitter

By Destiny Herbers, Flatwater Free Press

A glance at federal records shows the series of Nebraska farms listed as foreign-owned, though there’s no country attached and no hint that these farms with unassuming names might be related.

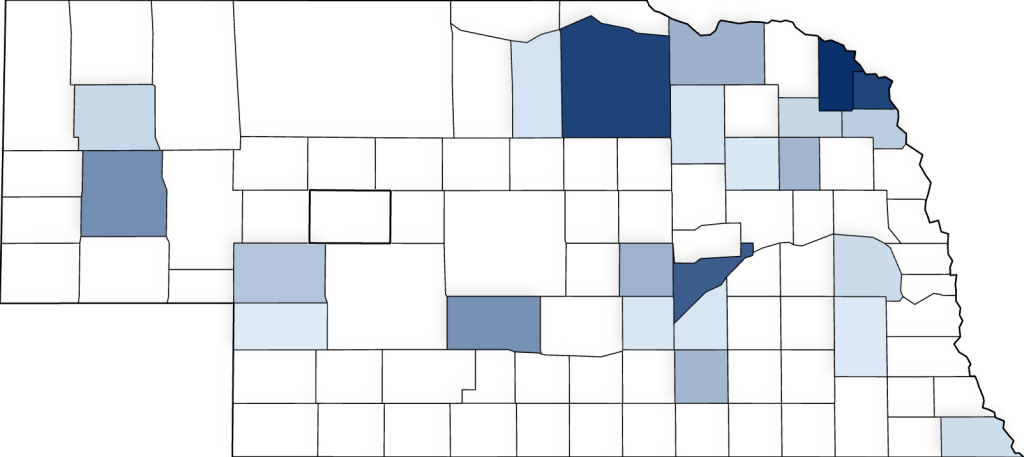

Willowdale Farms, Merrick County Farms, Dove Haven Ranch, Champion Valley Farm, Schroder Family Farms and many more are concentrated in northeast Nebraska but spread to the southeast corner and west nearly to Wyoming.

In Nebraska’s business records, they have one similarity: Each farm’s office address leads to a single-story brick building in the St. Louis suburbs, an office park housing a dentist, lawyers and, until recently, a farmland investment startup called AgCoA.

For years, AgCoA was owned by the Canada Pension Plan Investment Board, a government-owned group managing the retirement funds of 21 million Canadians.

But in 2017, the Canadian board decided to offload a half-billion dollar chunk of its American farmland portfolio — including all 22,830 acres of its Nebraska land.

The buyer of those unassuming-sounding Nebraska farms wasn’t publicly listed. Until now, the financial details of the transaction and the gargantuan loan he’s taken out against it have remained publicly unknown.

The buyer’s name: Bill Gates.

Tangled web of Gates

The billionaire who co-founded Microsoft has, in the past six years, spent more than $113 million buying Nebraska farmland.

The Flatwater Free Press analyzed five years of land sales data, between 2018 and 2022, originally gathered by a University of Nebraska-Lincoln College of Journalism and Mass Communications data journalism class.

If that data had included the year 2017 — when Mt. Edna Farms, the Gates-owned company that made that massive purchase from the Canadian pension board — then Gates would have been the top buyer of Nebraska ag land by money spent. Since 2017, he has spent more than double the second-place buyer.

Gates’ farmland is held by more than 20 shell companies spread across the country.

Some lead back to a P.O. Box in Kirkland, Washington, the city where Cascade Asset Management, which manages all Gates’ investments, is headquartered.

Others are linked to Lenexa, Kansas and Monterey, Louisiana, population 371, where reporters have previously traced Gates’ operations.

These limited liability companies, buried under layers of business names, overlapping employees and addresses in at least three states, form a network more tangled and opaque than the one created by The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, which is buying a giant amount of Nebraska ranch land.

Because it’s hidden, Nebraskans living and farming in communities where Gates is among the largest landowners are often unaware that one of the world’s richest men owns the cornfield down the road.

Gates now owns around 20,000 acres of farmland across 19 counties in Nebraska after selling some land in recent years. He owns the largest chunk of land, about 8,500 acres, in Holt County.

“I think if you ask on the street, who owns Mt. Edna Farms, nobody’d even know what it was,” said Bill Tielke, chair of the Holt County board. “So it’s not like people realize that he does own that much land in Holt County.”

Mt. Edna has a farm manager in Holt County, Tielke said, and local people work for the farm and rent the ground. Tielke has worked as a crop adjuster for local farmers who rented Mt. Edna’s land, and said that if they hadn’t told Tielke that Gates bought the land, he wouldn’t have known.

“I don’t remember it throwing up any bells or whistles or anybody even saying anything about it,” Tielke said.

The Nebraska Farm Bureau, through spokesperson Cassie Hoebelheinrich, declined to comment on Gates’ farmland ownership.

“This is an issue we really don’t follow and isn’t a priority for us,” Hoebelheinrich said in an email.

Gates’ land ownership has been the source of much rumor, and some concern, in Nebraska, partly because of his connections to the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, which runs programs addressing issues of global public health, sustainability and climate change.

If Gates’ land was given to a nonprofit — potentially making it exempt from property taxes — it would “decimate” the counties involved, state Sen. Tom Brewer, a Republican whose district covers 11 rural counties in central and northern Nebraska, said in an email.

“It would force action from the Legislature to protect the counties,” Brewer wrote.

But the farmland is one of Bill Gates’ financial investments, said the company that manages those investments, not part of the Gates Foundation’s portfolio.

“The investments that Cascade makes in Nebraska farmland are not connected with the agricultural or climate initiatives of the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation,” a Cascade spokesperson said in an email.

Cascade Asset Management declined to answer further questions about its Nebraska farmland purchases and the structure of the affiliated limited liability companies (LLCs).

Gates himself recently publicly reinforced the idea that his farmland purchases are investments.

“The decision to buy this land was made by people who help manage my money so that we get a good return so that the Foundation can buy more vaccines,” Gates said on a November episode of Trevor Noah’s podcast. “And they saw that if we could invest in land and (improve) the productivity of that land, that it would have a good return.”

Buy, borrow, die

Gates doesn’t simply receive rent checks from his Nebraska farmland. He’s also using it to borrow staggering sums of money.

Three days before Christmas 2021, Mt. Edna Farms filed paperwork with Dawson County, clearing the path to use a part of Gates’ land as collateral. Gates’ LLC then took out two loans against his Nebraska farmland.

The total of those loans: $700 million.

The obvious question: Why is Gates, who Forbes deemed the world’s richest man 18 different times between 1995 and 2017, using Nebraska farmland to take out a $700 million loan?

Using IRS data, the news outlet ProPublica estimated Gates’ total average annual income between 2013 and 2018 was $2.85 billion, with an average federal income tax rate of 18.4%. That income primarily came from sales of Microsoft stock, which is taxable.

But extremely high net-worth individuals like Gates often use a strategy of borrowing against their assets — like land — if they want spendable money.

Selling those same assets would generate taxable income, said Adam Thimmesch, a University of Nebraska College of Law professor specializing in business and tax law.

“If you can hold those assets until you die, all of that taxable gain goes away, so the ideal tax planning technique, if you’re wealthy enough to be able to do it, is to invest in those appreciating assets,” Thimmesch said.

If certain conditions are met, tax law allows someone to inherit the land and avoid paying taxes on the long-term appreciated value if they sell it, Thimmesch said.

In the meantime, ultra-rich Americans can borrow against their assets to fund their lifestyles or make other investments. Banks are happy to lend money for something like farmland, the law professor said, because there’s security in the value.

“Then on your death, your heirs can sell the property if they need to, to pay back the debt, and there’s just no tax liability anymore,” Thimmesch said. “So you can eliminate that entire layer of tax, while still kind of enjoying the benefits of being wealthy while you’re alive.”

To use this so-called “buy-borrow-die” method, Gates would need to place his Nebraska farmland in his own name before he dies or be the sole owner of Mt. Edna Farms LLC.

The corporate structure and official ownership of Gates’ various shell companies have never been publicly explained. It’s impossible to know now if his land would be eligible for the tax provision, Thimmesch said.

Cascade Investment declined to answer questions about the loan, and the management of Gates’ investments beyond confirming that they are not connected to the activities of the Gates Foundation.

Below the surface

Gates’ land ownership in Nebraska includes the valuable water beneath that land.

He has access through 191 existing wells, which add to the value of the land for farmers and investors alike by providing crop irrigation.

Gaining access to groundwater is often a priority for potential farmland buyers. If you own land in Nebraska, you have the possibility of accessing the underlying groundwater, but natural resource districts regulate how water is used.

“I’m sure that the NRD [Natural Resources District] is well aware (of Gates), and that every one of those wells is no doubt permitted and has associated certified acres and probably does some annual reporting to the NRD as well,” said Don Blankenau, a lawyer who provides water-related legal counsel to Nebraska NRDs.

Gates’ existing wells were transferred to Mt. Edna with the lump sum purchase of land in 2017, public records from the Nebraska Department of Natural Resources show.

“We don’t treat Bill Gates any different than Dean Edson or anybody else. They can have that land, but they don’t own the water,” said Dean Edson, director of the Nebraska Association of Resource Districts. “If they want to use the water, Bill Gates is gonna have to come get a permit.”

If you buy land in Nebraska without a well, there’s no guarantee your local NRD will grant a permit to dig one. But if the land already has a well, the NRD has likely already certified its use. The landowner, be it Bill Gates or Bill Jones, can continue to use that water so long as the use follows existing rules, Blankenau said.

“I’ve heard over the decades I’ve done this, people are always concerned that somebody’s gonna go out and buy a big tract of land in the Sandhills, and then transport that water away,” Blankenau said.

That’s nearly impossible, he said, because Nebraska has tight limitations on the transportation of groundwater, especially outside of state borders or as a commodity.

An investor like Gates moving large quantities of groundwater via pipeline or trucking operation would attract the attention of neighbors and the local NRD.

“If you extract groundwater out of the ground, carbonate it and add sugar to it, you’ve got soda pop, and you can move that all over the place. Same thing with beer, one of my law partners started brewing, and I always tease him that he’s exporting groundwater in the form of beer,” Blankenau said.

In Holt County, Gates’ operation has gone mostly unnoticed by neighbors and county officials. And the actual farming of that land has barely changed.

But Gates’ land buys still matter, said Tielke, chair of the Holt County board. The purchases of any large outside investor limit the opportunities for small farmers to break into the industry.

“I think it’s going to cause a lot of problems for future generations to get young people started,” Tielke said. “It’s getting pretty hard to compete with these guys that are coming here buying this land now.”

Originally published by Investigate Midwest.

Destiny Herbers, Flatwater Free Press, is a Roy W. Howard fellow through the Scripps Howard Foundation. She earned her master’s degree in journalism at the University of Maryland.

Flatwater Free Press reporter Yanqi Xu contributed to the data analysis used in this story. The series, “Who’s Buying Nebraska?” was made possible by a grant from the Center for Rural Strategies and Grist.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Children's Health Defense.

“© [2024] Children’s Health Defense, Inc. This work is reproduced and distributed with the permission of Children’s Health Defense, Inc. Want to learn more from Children’s Health Defense? Sign up for free news and updates from Robert F. Kennedy, Jr. and the Children’s Health Defense. Your donation will help to support us in our efforts.