Please Follow us on Gab, Minds, Telegram, Rumble, Gab TV, Gettr, Truth Social

Reprinted with permission Jane Hampton Cook Substack

On August 8, 2022, around 2 p.m., I finished an immersive edit of my latest book manuscript, War of Lies. As relieved as I was joyful to finish the edits that had been pulsating through my mind like a storm for three weeks, I flipped on the TV only to discover that the author who had most shaped my approach to writing history had died.

Author and historian David McCullough died on August 7, 2022, at his home in Massachusetts, just two months after losing Rosalee, his wife of 68 years. Regardless of how long he lived, he knew that he would never live long enough to fill the endless literary landscape of his mind.

Thanks for reading Jane Hampton Cook’s Substack! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.Subscribe

“I feel that what I do is a calling. I would pay to do what I do if I had to. I will never live long enough to do the work I want to do: the books I would like to write, the ideas I would like to explore,” McCullough explained in a 2007 interview.

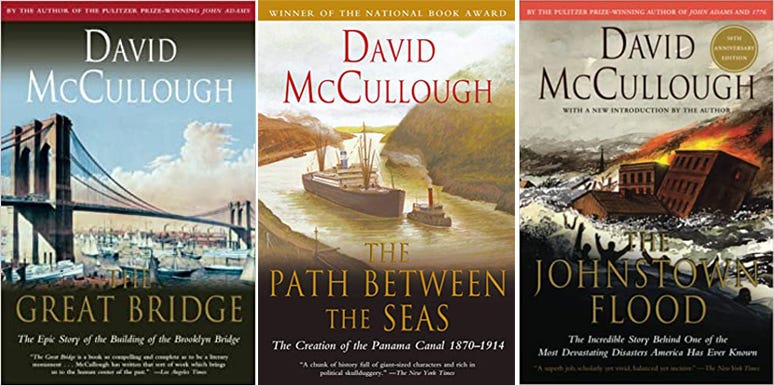

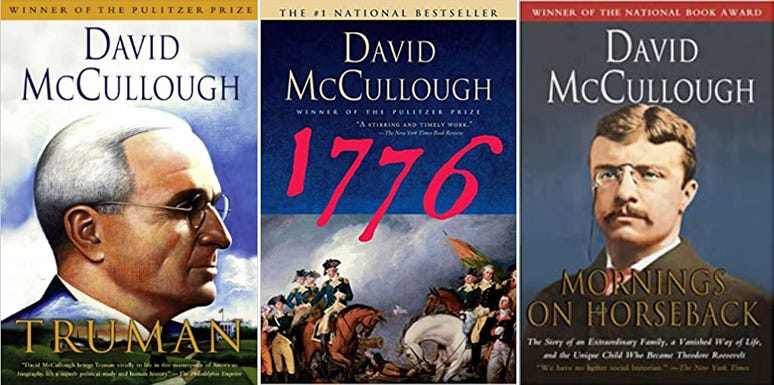

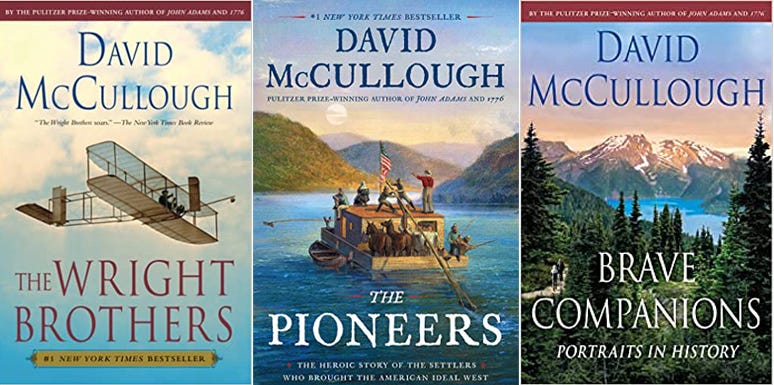

McCullough lived 89 years. He was the author of the Pulitzer-winning biography John Adams, 1776, Truman, Brave Companions: Portraits in History, and The Pioneers among many others.

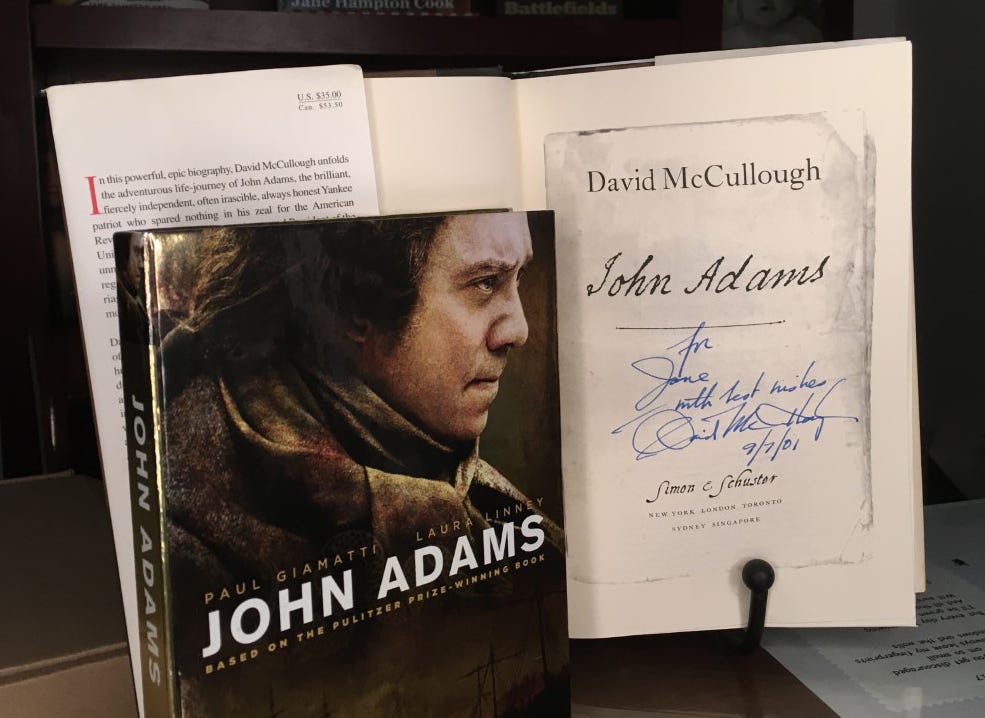

My memories of McCullough trace back to four days before the terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001, when my husband heard McCullough speak in Washington, D.C. on September 7. Kindly personalizing his inscription, McCullough signed a copy of John Adams, which you can see in the above picture.

By this time, I had already written my first book, which was a children’s historical fiction book about Sam Houston’s opposition to both slavery and Texas joining the Confederacy. I had planned to leave my job as a White House webmaster at some point to become a mom and pursue writing more books. I hadn’t yet decided whether to pursue fiction or nonfiction.

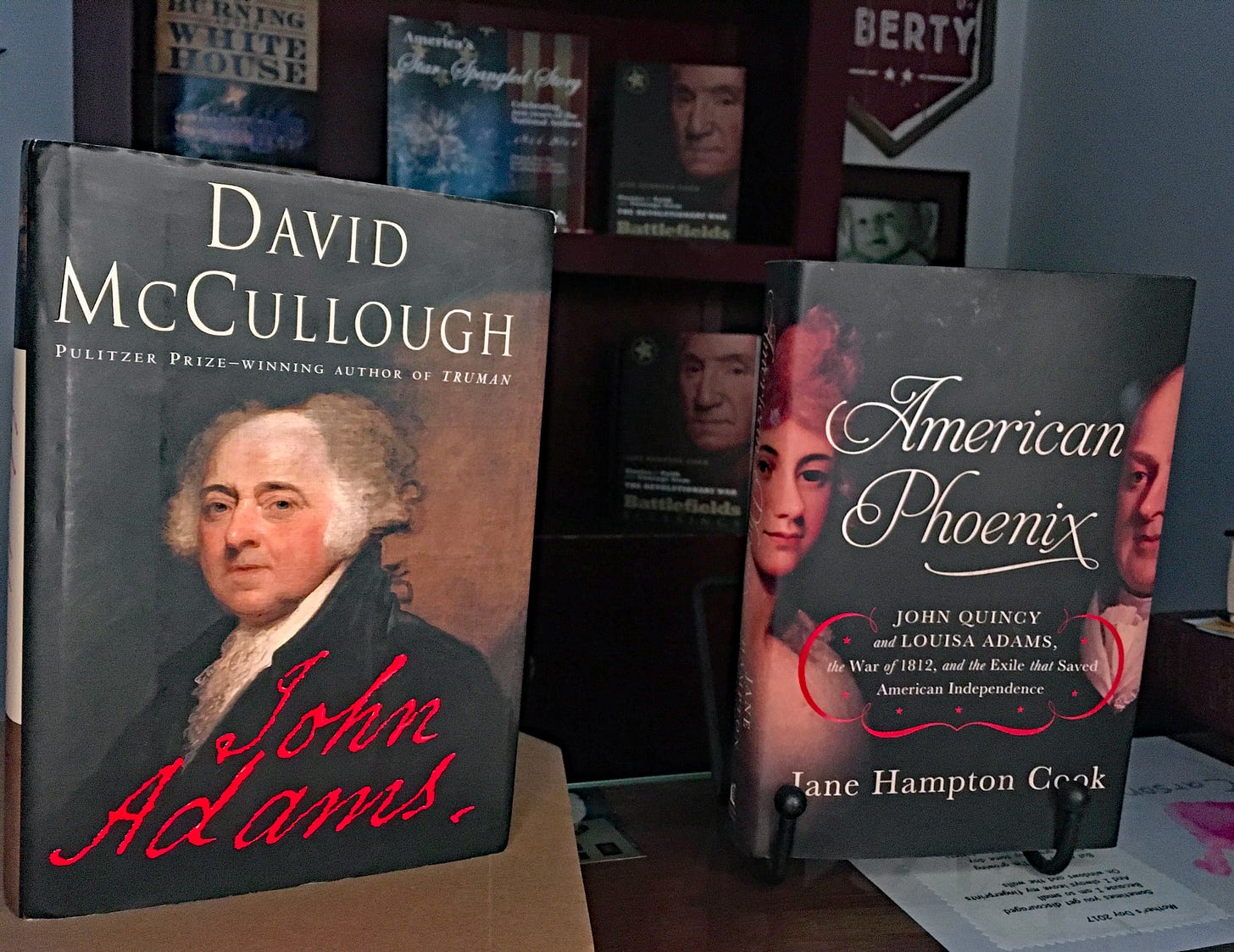

Reading McCullough’s John Adams inspired me to write literary nonfiction instead of historical fiction when I left the White House in March 2003. I was so intrigued by John and Abigail’s humanity in John Adams that I wrote a book about the second generation of the Adams family, John Quincy and Louisa Adams, in American Phoenix. I also adapted McCullough’s approach to endnotes, which gives the reader references while maintaining a nice appearance. McCullough’s daughter, Dorie Lawson, kindly corresponded with me so I could send him a copy of American Phoenix.

What I loved about McCullough’s work, is that although he wrote nonfiction, his narratives flowed and made you feel that you were in another time and place. He explained his approach in a revealing 2007 interview with the chair of the National Endowment for the Humanities.

“People ask, ‘Are you working on a book?’ I say, ‘Yes.’ But I really want to say, ‘No, I’m working in a book. I’m inside it.’ I want to be inside the time,” McCullough noted of his ability to take his mind and hence, his readers, into other worlds.

His immersive process is evident in his first book about the 1889 Johnstown flood. McCullough and his wife had visited the Library of Congress, where they saw a new display of photographs from the Johnstown flood. Growing up not far from Johnstown in Pittsburg, Pennsylvania, McCullough had heard about the flood all of his life, but these photographs were so disturbing that he wanted to read more.

The books he read left him unsatisfied because they failed to capture the awestruck emotion he’d felt after seeing the destruction in those photographs. Hence, he decided to write his first book. McCullough’s The Johnstown Flood was published in 1968.

A few years later, his book about the creation of the Panama Canal, The Path Between the Seas, won the National Book Award. His narrative wasn’t merely an exposition of this technological wonder. Rather, he wrote about the underlying human drama of the men and women who fulfilled a 400-year vision of building the Panama Canal, which transformed the world of shipping. Their heroic successes, failures, political power plays, and engineering feats made this book intriguing.

To McCullough, human nature, not word tricks, made stories about the Panama Canal and other places relatable.

“I have to have the form in mind before I can write the book. All you are trying to do is to make it as interesting and as human as it really was. You don’t have to gussy it up. The pull, the attraction of history, is in our human nature. What makes us tick? Why do we do what we do? How much is luck the deciding factor?” McCullough reflected.

The Path Between the Seas caught the attention of President Jimmy Carter, who invited McCullough to the White House to discuss the Torrijos–Carter Treaties that later transferred control of the canal to Panama.

For McCullough, heroes and heroines gripped him more than the location or era.

“I’m drawn particularly to stories that evolve out of the character of the protagonist,” McCullough said in 2007.

From writing about The Wright Brothers to Theodore Roosevelt in Mornings on Horseback, McCullough's attraction to strong protagonists led him to dive into the lives of many American heroes throughout his career. A secret behind his success was his understanding that the past was someone else’s present.

“First of all, you can make the argument that there’s no such thing as the past. Nobody lived in the past,” McCullough explained.

He understood that the people he wrote about in his book, 1776, and other eras didn’t live in a gray landscape. Their reality was a full-color panorama with an unknown ending.

“They lived in the present. It is their present, not our present, and they don't know how it’s going to come out. They weren’t just like we are because they lived in that very different time. You can’t understand them if you don’t understand how they perceived reality and you don’t understand that unless you understand the culture. I wish we had a less fancy word than ‘culture,’ because it sounds too pretentious.”

This idea is something I’ve tried to keep in mind, especially when chronicling a person’s timeline. In mid-December 1776, when George Washington wrote his brother that the game was pretty near up, he hadn’t yet crossed the Delaware River and victoriously attacked the British outpost guarded by Hessians at Trenton. In hindsight, the Battle of Trenton was a turning point in keeping independence alive but George Washington didn’t have that perspective at the time. Keeping track of what a person knew, and when they knew it, is important to maintaining an “in the moment” feel for a book about the past.

McCullough’s ability to bring strong protagonists into sharp, near touchable focus led to earning Pulitzer Prizes and film productions of John Adams and Truman on HBO and receiving the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2006 from President George W. Bush. These accomplishments also followed a surge of patriotism and an increased interest in history that took place for several years after the September 11 terrorist attacks.

“Since September 11, it seems to me that never in our lifetime, except possibly in the early stages of World War II, has it been clearer that we have as a source of strength, a source of direction, a source of inspiration--our story. Yes, this is a dangerous time. Yes, this is a time full of shadows and fear. But we have been through worse before and we have faced more difficult days before. We have shown courage and determination, and skillful and inventive and courageous and committed responses to crisis before. We should draw on our story, we should draw on our history as we've never drawn before.”

Perhaps the strongest ingredient in McCullough’s ability to take unformed clay and sculpt literary masterpieces about our nation’s story is simply joy. Writing history brought him happiness.

“To me history ought to be a source of pleasure. It isn’t just part of our civic responsibility. To me it’s an enlargement of the experience of being alive, just the way literature or art or music is.”

One of his concerns, which I shared, in the first decade of the 21st Century was historical illiteracy. At this time, in 2007, McCullough had been lecturing at colleges for 25 years.

“From my experience I don’t think there’s any question whatsoever that the students in our institutions of higher learning have less grasp of American history than ever before. We are raising a generation of young Americans who are, to a very large degree, historically illiterate. It’s not their faults. There’s no problem about enlisting their interest in history. None. The problem is the teachers so often have no history in their background.”

McCullough believed that often teachers of history in public schools had no background in history but were education majors who had to teach history. If a teacher doesn’t love the subject they are teaching, then students won’t love it either.

“If we think back through our own lives, the subjects that you liked best in school almost certainly were taught by the teachers you liked best. And the teacher you liked best was the teacher who cared about the subject she taught.”

Beyond motivating teachers to have passion for our nation’s history, McCullough feared that historical illiteracy would lead to a dangerous place.

“If we don't know who we are, if we don’t know how we became what we are, we’re going to start suffering from all the obvious detrimental effects of amnesia.”

McCullough believed historical amnesia should anger Americans as much as concern them.

“It’s not just something that we should be sad about, or worried about, that these young people don’t know any history. We should be angry. They are being cheated and they are being handicapped, and our way of life could very well be in jeopardy because of this.”

His words were prescient. Unfortunately, since McCullough’s 2007 interview, our way of life is now in jeopardy because of the hard-left turn that has taken place over the past 15 years. Just as communists sought to tear down Russia's history and culture, so athletes began kneeling for the national anthem, which was inspired by a battle that nearly cost America its independence in 1814, at professional sporting events.

In recent years, neo-Marxist agitators have vandalized, torn down, or forced the removal of statues of historical figures across the United States.

Likewise, the New York Times produced the 1619 Project, which initially falsely asserted that the birth of the United States of America was not in 1776 but in 1619, when the first African slaves arrived in Virginia. As searching by keyword across historical newspapers shows, the phrase United States of America was not used in newspapers until the Continental Congress issued the Declaration of Independence on July 4, 1776. The United States appeared as a phrase more than 600 times in newspapers from July to December 1776, proving that the birth of the USA was indeed in 1776.

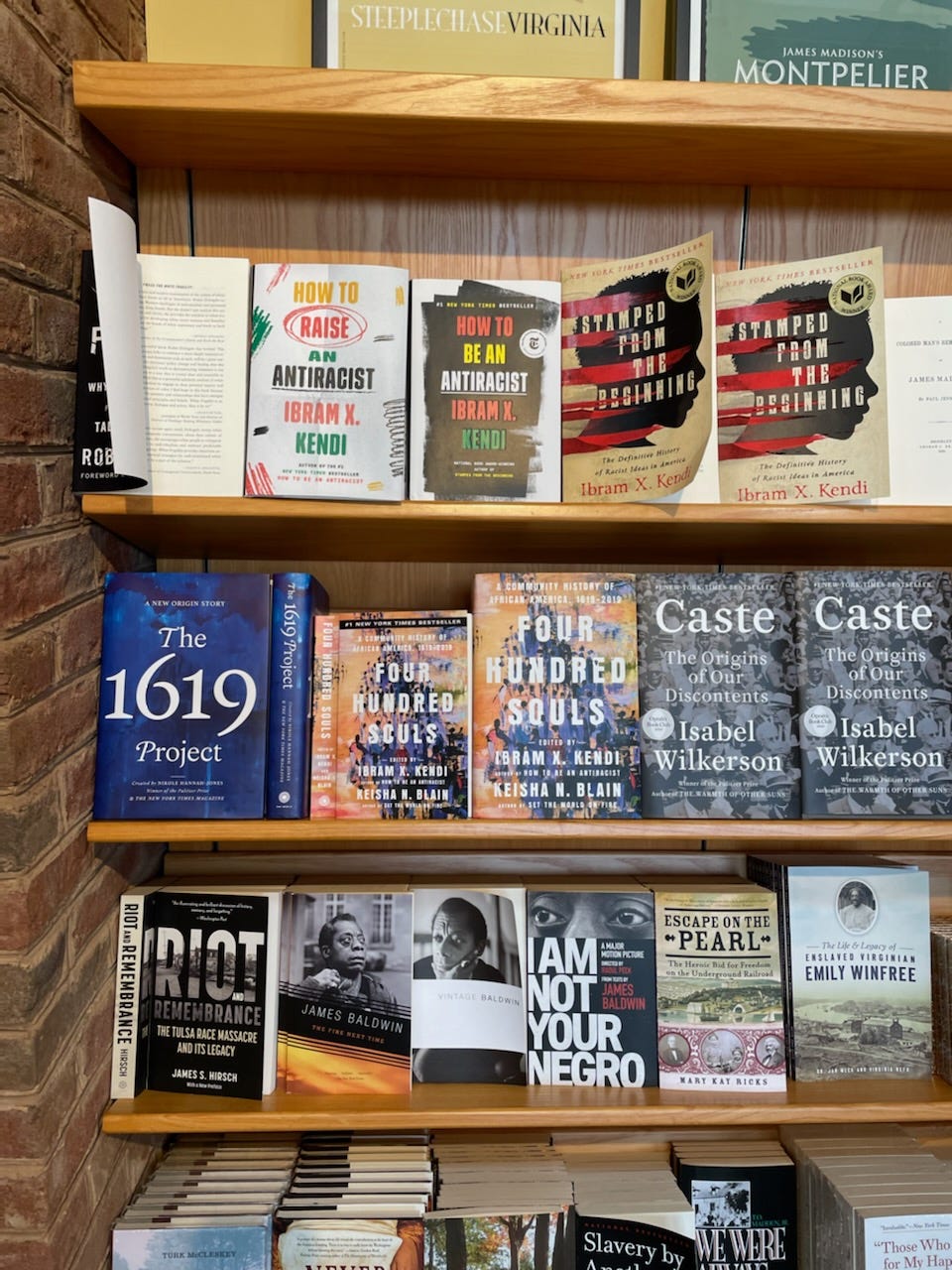

Though the 1619 Project was panned by historians and educators of multiple races and ethnicities for its false premise and misleading information, schools and museums across the nation have nonetheless incorporated the neo-Marxist doctrine and tenets of the 1619 Project into their curriculum.

Recently, wealthy leftist donors to James Madison’s historic home, Montpelier, have forced 1619’s adoption into their bookstore (pictured below) and tour narrative, as the New York Post has reported. For sure, slavery should be taught and studied, but it should be done with accuracy and perspective without erasing the contributions of the father of the Constitution and others.

Despite today’s serious problems, what tickled me in reading McCullough’s 2007 interview for this substack article, is that he brought up a John Adams quote that I love and had recently used in the introduction for my unpublished manuscript, War of Lies.

To address the importance of knowledge in preserving liberty, McCullough quoted a paragraph that Adams had written in 1780 for the Constitution of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts.

“Wisdom and knowledge, as well as virtue, diffused generally among the body of the people being necessary for the preservation of their rights and liberties” -- you have to have wisdom and knowledge as well as virtue to preserve your rights and liberties-- “and as these depend on spreading the opportunities and advantages of education in various parts of the country, and among the different orders of the people”--in other words, everybody-- “it shall be the duty”--the duty-- “of legislators and magistrates in all future periods of this commonwealth to cherish the interests of literature and the sciences, and all seminaries of them. . .”

McCullough applied Adams’s idea that knowledge must be diffused through education to preserve liberty. In my latest book manuscript draft, I chose an earlier 1772 version of Adams’s quote and applied it to the need for truth in our media no matter the generation.

Truth must be disseminated in both education and the media in order to preserve the intellectual and moral character of Americans. David McCullough’s legacy as an author and historian of literary nonfiction and biography gave millions of readers the opportunity to discover truth in history through relatable, real American heroes and heroines.

Mr. McCullough, thank you for inspiring me and for being a writer’s writer. You will be missed and your words will live on. May God Bless your legacy.

Jane Hampton Cook

Jane Hampton Cook is a presidential historian, former White House staffer and author of 10 books, including Stories of Faith and Courage from the Revolutionary War. Janecook.com.