Please Follow us on Gab, Minds, Telegram, Rumble, Gettr, Truth Social, Twitter

What do the following famous artworks, top in their respective museums, have in common— Jasper Johns's "Three (American) flags" (1958), at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York; Warhol's "Marilyn Monroe diptych" (1962), at Tate Modern in London; and Piet Mondrian's last work "Victory boogie woogie" (1944), in the Hague? These iconic works all were officially based in Meriden— the town where I grew up—until 1980, 1980 and 1988 respectively— in the Burton and Emily Hall Tremaine Collection. This was in the sphere of Burton’s Miller Company while the couple lived in Madison and New York after World War II.

In 1988, a year after Emily passed away, a selection from the hundreds of artworks in their collection was sold at Christie’s auction house in New York. There was full-on media coverage reporting on the sale across the US and beyond. So, this was a great success, culminating in a celebration of Emily’s entrepreneurial life in the arts— and partly out of Connecticut, right?

Well yes, and also no. Regarding after 1945, sure. But you see, before WWII, Emily (1908-87) was in the anti-Nazi / Nazi fight, not in Europe, but in California. For well over the past two decades, it has been unclear what was actually going on there and around Emily—and that history is as messy as it gets, as decadent as it gets, and as dangerous and muddled as it possibly can get.

In a summary in the audio introduction below, over 4,000 sources in, I talk about Emily’s life with anti-Nazi / Nazi intrigue in California. There were serious threats against German passport holders—which she and her first husband were, her first husband died in a violent plane crash, and as a social celebrity Emily wore a million in diamonds reported in the national press (worth $14m+ today). Some even call Emily today, “the original It Girl”. Around Emily in California there were some Nazi agents, anti-Nazis, the FBI, a German consul-double agent, and Jewish emigrés that fled Europe. US Naval Intelligence was surveilling Nazi activity in southern California and understaffed with the escalating threat, so they recruited civilian “eyes and ears” spies.

But where was Emily exactly in all of this?

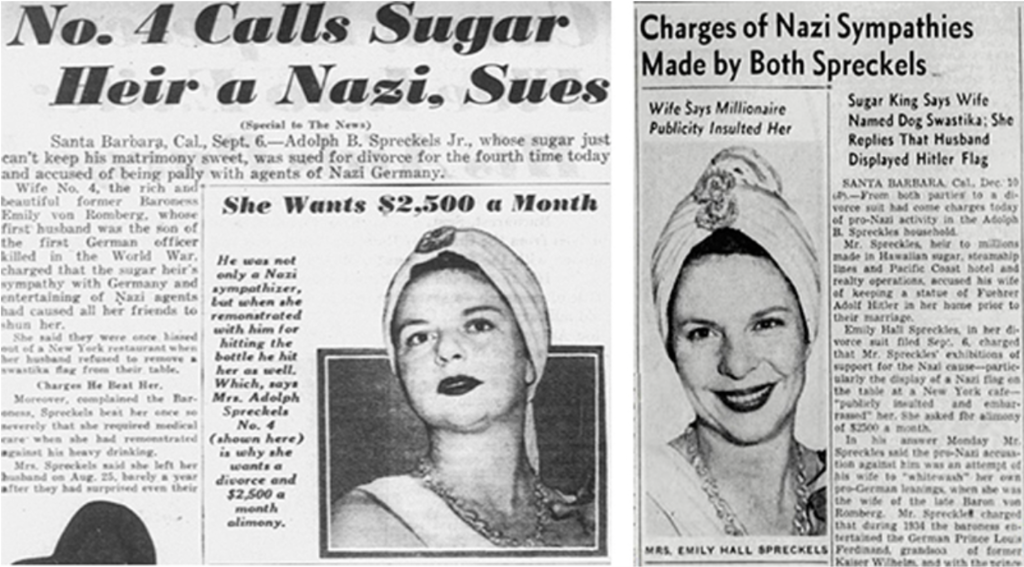

In September 1940, Emily initiated a shocking divorce action with her year-long second husband. It was known as the “He’s a Nazi, no, SHE is” case, and it occupied the national US media for two months leading up to the 1940 election.

After WWII, people in New York and Connecticut knew about her California life, to some extent. It had been in the papers with photos of her. For some, she was clearly the fun and crazy contemporary art lady from California. To the blue bloods of Connecticut, who knows? Maybe they thought of her as an exotic bird from the West Coast, that they found entertaining— and then not.

And what about the three famous artworks, now in three countries, that Emily owned that were officially based in Meriden? I’d argue they all relate to Emily’s crazy 1933-45. “The American flag” was mentioned passionately by Emily in a secret deposition that I unearthed—while she was under intense questioning with a Nazi tinge. In the 1960s, it was above her couch in her Madison living room. The “Marilyn Monroe diptych” shows “rise” and “fall”, really destruction, in the media. Well, Emily lived through that in 1935-41. This painting wasn’t in her house or flat in New York— but in storage or loaned to museums.

Then there’s “Victory boogie woogie”, unveiled by Queen Beatrix after the Dutch government paid $40 million for it in 1998, which created a national scandal for the price paid, in a wave of media coverage that Emily certainly knew how to spin back in the 1930s. “Victory” was Emily’s mental ticket out the chaos and conflict of World War II— and a kind of spiritual window into the world of Modernism.

“Victory” was Emily’s favorite artwork, and usually in her New York living room. She wouldn’t part with it until after her death. Officially located in Meriden from 1944-87, these days the painting is located in a museum about 15 miles north of me in the Netherlands, where I’ve lived for over two decades.

“Victory” is often in its own room. I call it “Emily’s chapel”. I occasionally do go there. It’s always a multi layered experience—and very intense.

Back to the 1930s. Was Emily pro-Nazi, a US patriot-spy, or both? As it turns out, Emily is looking more and more like an “eyes and ears” spy for US Naval Intelligence. It was right in her family in SoCal. Recent generations didn’t know. A secret deposition of Emily, found buried in the court record of her divorce action in California, was a key starting point with information and leads. A certain declassified intelligence document will confirm, and my group is on it. Watch this space.

Listen to:

Nazis in California: Emily Hall Tremaine fights back (book preview)

Was Emily pro-Nazi, a US patriot-spy, or both?

13m narrative | 15m discussion

| 1928 | Emily married Max Converse von Romberg. He had German nationality and a minor title, and was a grandson of the famous banker Edmund Converse of Greenwich. Max's mother was Antoinette, a sort of Barbara Hutton type living mainly in Europe. |

| 1933 | Hitler took power; Emily filed for divorce. |

| 1934-1936 | Emily and Max reconciled and started an anti-Nazi leaning magazine; they became social celebrities in the national media, reported on regarding their personal life and the magazine; in 1935, Emily named her new dachshund Swastika while putting Jewish names prominently on the front and back covers. |

| 1937-1938 | An attempt to extort Max’s best friend was made by a British Nazi, who planned to fund the assassination of ~20 leading Hollywood Jews. There was a trial with national media coverage, and the Nazi was forced to return to Britain. |

| 1937 | Max began building a new house with a swastika on it. Not long afterwards he quietly took American citizenship, effectively cancelling his German citizenship and officially his title. [Emily later insisted the swastika was Indian (or native American)—and reverse from the Nazi swastika] |

| 1938 | Max died in a suspicious plane crash in New Jersey. He was flying the plane and it nose-dived into a river. |

| 1939 | Emily married sugar heir Adolph B. Spreckels, Jr. of San Francisco. |

| 1940-1941 | Emily and Adolph were in the “I’m not the Nazi, SHE is” divorce case reported in media waves across America into the 1940 election. Emily publicly supported Willkie and greater intervention in the European war. The case was later dismissed. |

| 1941 | The highest level of US Naval intelligence was publicly socializing with Emily in small group gatherings, reported in the press, after the craziness. The head of intelligence was Jewish, the then-famous Ellis M. Zacharias. This also included meeting Emily’s new friends after 1939, a European Jewish refugee couple. |

| 1945 | Right after the Yalta Conference, on her third attempt, Emily divorced Adolph, which this time he quickly agreed to; she then later married industrialist Burton Tremaine of Madison / Meriden and they began their life with art / design together. |